Hastings families in the 12th century: Part 2

Note

to researchers. This two-part article is written by me, Andrew Lancaster, begun

in 2014 with

the hope of assisting genealogical and historical research. But to make

sure it

does not simply add to confusion, fellow researchers are asked to

record

it as a source if they find something new (including new ways

of

putting things) that they wish to use,

and to include this information when passing on that information to

others (as should be done with all sources). Please also note that

because it is intended to be improved when possible, the text will

change over time, and therefore you should consider recording the

date

of accessing it in

your notes.

Keeping in mind the aim of informing, rather than

confusing, anyone with constructive feedback and suggestions is

also requested to

contact

me.

There are short in-line

references

to standard works, and to the small number of key works in the

bibliography. (Any authors or pages numbers appearing without explanation should be traceable there.) There are also some

footnotes where detail would distract.

I

have had helpful correspondence, but one person in particular who

should be thanked is Rosie Bevan, whose experience and knowledge helped

me improve both webpages.

More on what is known and what is not about the early Hastings families.

Part 1

explained how two Hastings families of the 12th century can be

distinguished, and how at the same time some connections can be at

least partly explained. The aim has been to define not only

which things are proven, but how they are proven, and also, maybe even

more important, whether the evidence that has survived can give us convincing explanations.

By the

end of the 12th century, one of those Hastings families discussed

so far, the lords of the Barony of Little Easton based in Essex, were

coming to an end of sorts. A son-in-law with a different surname,

Louvain, would take over the Barony. But their associates with the same surname,

the dapifers to the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, were still on the way up.

The Hastings family to be focussed

on now are ancestral to several important Hastings families who

remained politically important beyond the Middle Ages. Hastings Earls

of Pembroke and Huntingdon descend from them, and a large section of

the Complete Peerage (Volume

VI) is dedicated to them. They have many living descendants any place where there are people with

English ancestry, most

of whom have no idea of the fact.

The aim now is to make a link between a man named William de Hastings who

flourished in the 1160s, and already introduced on the first webpage, and

his eventual successor named Henry de Hastings who took over the family

inheritance in 1226 and married Ada de Huntingdon, an important heiress. This Henry's son,

also named Henry, is the first Hastings entry in the Complete Peerage, and was an ally of Simon de Montfort.

1. William de Hastings in the 1160s. How many people was he?

On the first webpage, Katherine Keats-Rohan's two books Domesday People (DP)

and Domesday Descendants (DD)

helped give a starting point. Her books are a standard reference,

aiming to

list people named in original documents in this period. They

often expose useful questions because of the "fresh approach" they take.

Relevant to the discussion now, as already mentioned

under pedigree 7 on the first page, Keats-Rohan made an

unusual distinction

between two men named William de Hastings, who are normally assumed to

be one man, but at the same time seemed to confuse both of them with

another man named William de Hastings who is generally considered

to be a

separate person:

- "Willelm de

Hastings dispensator" is the name Keats-Rohan gives (DD)

to the nephew and heir of Ralph de Hastings as dapifer (or seneschal,

both words sometimes translated as steward)

of Bury, who was also a steward of king Henry II. (The term

"dispensator"

which Keats-Rohan uses to name him refers to the specific type of office that King Henry II desribed him as having, sometimes

translated as "bursar".1.) From his uncle Ralph he received possessions

in Norfolk, Suffolk, Bedfordshire, and at least for a while in

Somerset.

- "Willelm

filius Hugonis de Hastings"

(William the son of Hugh de Hastings) is the name Keats-Rohan gives (DD)

to the son and heir of Hugh de Hastings and his wife Erneburga de

Flamvill, normally considered to be the same person as the man who was

a dapifer and bursar. From his parents he received possessions in Warwickshire and Leicestershire.

- William de Hastings of Eaton in Berkshire is given no separate entry in DD. He had

possessions in Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, in what was

apparently at least once referred to as the "Honour of Hastings". See VCH Berkshire: "The Oxfordshire land was at Westwell, Yelford and 'Alwardesbury'; that in Gloucestershire was at Southrop and Farmington."

This

surprising difference between Keats-Rohan's respected and methodical

summary, and the standard understanding of most genealogists, draws

attention to how little is certain in these generations. Keats-Rohan

starts from a limited number of strong sources, which we therefore need

to check next in more detail if we want to understand this. As will be shown, one important source in

this case is the Red Book of the Exchequer which covers 1166 in one major section (Volume I of the modern edition).

William de

Hastings "the dispensator"

The

first webpage already addressed one source of confusion. Despite a

generally cautious methodology, Keats-Rohan has a speculative theory

which

plays a role in making her conclusions so distinctive in this case.

One reason for not equating the dispensator with the son of

Hugh is that she proposed him to be the son of William fitz Robert,

lord of Little Easton in Essex (whose son Robert and brother Richard

both used the surname de Hastings). So for Keats-Rohan, he could not be

the son of a

Hugh. But as explained on the first webpage he was not the

son of William fitz Robert. Not only was that William's heir named

Robert de

Hastings, but also no

record could be found showing any William in this family after William

fitz Robert himself. Surnames seem to follow mysterious rules

sometimes

in this period, but the two families do seem to have been connected by

several marriages in the early 12th century, not only with each other,

but also with families using the surnames "de Flamvill" and "de

Windsor". (Indeed, as

Rosie Bevan has pointed out to me, later in the 12th century the

dispensator's sister Amabilia also married

a close relative of Robert de Hastings of Little Easton, Ralf de

Excestre, which the strict rules of consanguinity would have disallowed

if they shared a common ancestor as recently as Keats-Rohan

proposes.)

Nevertheless,

Keats-Rohan's distinction raises the real question of whether it is

really obvious that the dispensator is the son of Hugh, as stated

by all the authorities who dealt with this in the past. If it was obvious, then how could Keats-Rohan even propose

this hypothesis? It would not be the first time that a careful review

of the sources exposes problems in respectably published medieval

pedigrees.

Going through the citations allocated to "the dispensator" William de Hastings by Keats-Rohan:

- First, Keats-Rohan decides not

to allocate any entry in the 1161/2 Pipe Roll to this William, but

seems to suggest that this should be considered. That roll mentions a William

de

Hastings once in East Anglia (Norfolk/Suffolk) and twice in London, and

these would be obvious

places for him to be, as someone with land in East Anglia and a

presence at court. Instead she allocates these to William fitz Robert

of the Barony of Little Easton who died about this time (and who she thinks

to be his father). The first webpage explained doubts that

William fitz Robert ever used the surname Hastings, after examining

each

Keats-Rohan citation for him. So

in fact one or more of these 1161/2 sightings may well have been the

dispensator. And Keats-Rohan specifically states that this is

a possibility, saying

that it is hard to distinguish the dispensator and William fitz Robert

until

after 1162. By comparison, Eyton in his Henry II itinerary says

that William the steward (and dispensator) starts appearing in royal records already in

1159, after Ralf his uncle stopped appearing 1158.

- In 1166 Keats-Rohan says William held five fees of Bury St Edmunds (Red Book I, pp.392-4). And she gives another reference as Bury Charter number 89

(Douglas),

which is Henry II's grant to his steward (dispensator) William de

Hastings of the dapifership of Bury St Edmunds, which came with five

knight's fees, a position that had been held by his paternal uncle Ralf

de Hastings.

Henricus

rex Anglorum et dux Normannorum et Aquietanorum et comes Andegauorum

archiepiscopis. episcopis. comitibus. baronibus. iustic'.

uicecomitibus. et ministris et omnibus hominibus suis francis et anglis

salutem. Sciatis me concessisse et carta mea confirmasse Willelmo de Hastyngs dispensatori

meo

dapiferatum sancti Edmundi. Quare uolo quod idem Willelmus et heredes

eius habeant et teneant dapiferatum illum bene et integre et in pace

cum omnibus pertinenciis eius in liberacionibus et feodis et

innominatim cum Legata et Bluneham et aliis locis et rebus eidem

dapiferatui pertinentibus sicut Radulfus

patruus eius

eum melius habuit et tenuit uel Mauricius

auunculus suus eiusdem Radulfi.

Testibus. Willelmo Malet dapifero. lose [sic] de Baillol. Alano de

Nouilla. Willelmo de Lanuolei. Hugone de Loncamp'. Hugone de

Gondeuilla. Hugone de Piris. Waltero de Donstanuilla. Roberto filio

Bernardi. Per manum Stephani capellani et cantoris mei. Apud Porcestram.

We

know that the lands (5 knights' fees in total) inherited with the

dapifership included not only Lidgate in Suffolk, and Blunham in

Bedfordshire ("

Legata et Bluneham"

mentioned in this grant), but also Herling, Tibbenham and Gissing in

Norfolk. Maurice

de Windsor, the dapifer before Ralf, whose wife was a member of the

Little Easton Hastings family, received Lidgate and Blunham as

part of his dapifership inheritance granted by Abbot Abbold between

1115 and 1119, and confirmed by King Stephen. In his grant, the abbot

also added the 2 knights fees of lands that had belonged to Ivo de

Gissing. (See Douglas Bury Charters

108 and

109. Jocelin of Brakelond's

description of these lands shows that they continued to be treated

differently as one bundle of inheritance, distinct from Lidgate and Blunham, which were worth 3 fees.)

- In the Pipe Rolls of 1163/4, 1164/5, and 1165/6 Keats-Rohan says William de Hastings the dispensator accounted for terra data

at Witham in Somerset. As discussed on the first Hastings webpage,

indeed, William also appears to have inherited this manor from his

uncle Ralf de

Hastings, the queen's steward, along with his dapifership of Bury. It

seems to be something Ralf himself was granted in his lifetime. Ralf

disappears from the Pipe Rolls records about 1162. In 1162/3 Ralf is

replaced by his widow Lascellina de Trailly in Fordham, Cambridgeshire (another grant made in his lifetime),

while in Whitham,

William indeed replaces Ralf in 1163/4. It seems relevant to note that

William only held Witham until 1167/8 (a Pipe Roll not cited by Keats-Rohan). Was he dead after that? Eyton in his Henry II itinerary also says he stops appearing in royal records in 1168.

- The

sourcing notes of Keats-Rohan also indicate another proposed sighting

in the Red Book in 1166, in the Honour of Clare in Suffolk (Red Book I, pp. 403-7). One entry says "Radulfus Hast. ij partes militis" (possibly a member of the Little Easton family), another says "Willelmus de Hastinges tenet xx librates terrae et j militem feodatum, de quibus non facit servitium nisi j militis". (The details of this entry are discussed by experts in such things, but in any case it seems he was paying for one and a half knights fees. His presence in this Barony makes sense. In a paper on the estates of the Clare family by Jennifer Clare Ward,

(p.321) the heirs of Henry de Hastings held a group of lands under the

Clares (Gloucester): Kelling and Salthouse in northern Norfolk, and Ashboking,

Cretingham, Helmingham and Otley in Suffolk. And earlier, Ralf

de Hastings the previous dapifer had granted rights in Otley to the

nuns of Wix (Bacton charter 8), so that property at least may have previously been held by Ralf.

More questionably:

- Keats-Rohan also says he held half a fee de novo at Compton, Surrey, of his kinsman William of Windsor (Red Book I, pp. 315-16).

I think the connections of the Hastings who lived in this period under

the de Windesors are not clear. William de Eton who held "Budenfunt" in the same record, surely West Bedfont,

near Heathrow, seems reminiscient of William de Eton or Hastings

in Eaton Hastings in Berkshire, but is perhaps not the same person.

(Given that they live in two places call Eton or Eaton, the name

coincidence is easy to explain.) The Compton

Hastings is even harder to connect convincingly to

anyone.

- Another doubtful citation is Charter 10, Gervers (1996), Cartulary of the Knights of St John, II.

This document mentions the templar master Richard de Hastings, who was

an

important contemporary of William de Hastings, and like him appears in

various records of Henry II. Although a William de

Hastings is mentioned in the charter then, as someone who had granted

land in London, it is hard to use this

charter to distinguish men of the same name, or to prove

kinship. Richard could have been a member of the Hastings family

of Little

Easton for example. In a Cambridgeshire grant he named a Robert de

Hastings as a kinsman, which is a name more typical of that family. It

is even possible that the templar could

consider both these Hastings families to be kin in a way.

- Also, Keats-Rohan associates the

dispensator with the Oxfordshire and Berkshire Pipe Rolls records for

1164/5. This will be discussed further below, but this clearly refers

to the Hastings family in Eaton Hastings in Berkshire.

"Willelm

filius Hugonis de Hastings"

This

William is associated with lands in Warwickshire and Leicestershire by Keats-Rohan, because of his parents.

(Several of the properties were held by a man called Robert the

Dispensator at the Domesday survey in 1086. In the 12th century the

Hastings were not his main-line heirs, and they were not overlords of

these manors, but it is tempting to think that there is a link.)- Keats-Rohan

allocates Pipe Rolls mentions of William de Lancaster in Warwickshire

and Leicestershire (generally these counties were handled together for this type of administration) as belonging

to "this" William, mentioning sightings there between 1158/9 and 1164/5.

- In 1166, Keats-Rohan says he held two fees of "Robert" de Ferrars (sic) at Red Book I p.338. This leads us to the section of Derbyshire, for William Count Ferrars, where we find:

"Henricus de Cuningestone, feodum j militis, quae duo tenet Willelmus

de Hastinges". Congerstone, where this tenant's surname came from, is near Shackerstone.

- Given the error of naming Count Ferrars Robert, Keats-Rohan perhaps also intended to draw attention to the holding under Robert Marmium in the Red Book p. 327 under Warwickshire in 1166, 1 knights fee by old enfeoffment.

More questionably:

- Keats-Rohan allocates a Northampton sighting, 8HII (1161/2).

Like the William de Hastings in Compton, mentioned above in 1166, there

seems to be no clear hypothesis yet to link this sighting to another

family.

- Also in 1166, Keats-Rohan claims to find this William de Hastings under Count William of Gloucester one fee de novo. pp. 288-92. I see only "se tertio

milite, de dominio". This

also looks like the family of Eaton Hastings in Berkshire, to be discussed below.

2. The successors in the 13th century

For William de Hastings,

the dapifer and steward, Keats-Rohan shows these references to represent

later generations, continuing the inheritance: - In 1200 a William de Hastings held

five fees of Bury at Lidgate, Blunham (Bedfordshire), West Harling,

Tibenham and Gissing, in Norfolk (Jocelin of Brakelond, Butler ed., p.120. For the Oxford paperback version see here).

These are

indeed the same five fees as above in 1166, but it is a new William.

One question to examine here will be the evidence for what the exact

relationship was to the old William.

- Around 1224 a William de Hastings held the

serjeanty of the king's dispenser ("tenet per sergantiam dispensarie

regis") in Norfolk and Suffolk (Fees, 346). More records of this can be

found, which show that the manor held was Ashill. This is the same "new William".

- Later, in 1226/8 and 1236 Henry de Hastings answered for the same serjeanty at Ashill in Wayland hundred, Norfolk, (Fees, 387, 402, 592). That Henry was the name of the son and heir of the "new William" is a fact we can confirm from the Fine Rolls:

10/52 (26 December 1225)

26

Dec. Winchester. Concerning taking lands into the king’s hand. Order to

the sheriff of Warwickshire and Leicestershire to take into the king’s

hand all lands that William of Hastings held in chief of the king and

the lands that he held of others in his bailiwick, and to keep them

safely until the king orders otherwise.

10/83 (28 January 1226)

28

Jan. Marlborough. For Henry of Hastings . To the sheriff of

Warwickshire and Leicestershire . Henry of Hastings has made fine with

the king by 50 m. for having seisin of all the land that William of

Hastings, his father, whose heir he is, held of the king in chief, and

that falls to Henry by hereditary right, and the king has taken his

homage. Order that, having accepted security from Henry for rendering

the aforesaid 50 m. to the king for his relief at these terms, namely

12� m. at Easter in the tenth year, 12� m. at Michaelmas, 12� m. at

Easter in the eleventh year, and 12� m. at Michaelmas in the same year,

he is to cause him to have full seisin without delay of all the land

that the aforesaid William, his father, held of the king in chief in

his bailiwick which were taken into the king’s hand by his order . He

is, moreover, to cause the executors of the testament of the same

William to have the chattels found in the same lands formerly of the

same William, saving to the king his debt if he owed him anything. The

king has ordered the sheriffs of Shropshire, Bedfordshire and Norfolk

and Suffolk that, having received his letters testifying that he has

received security, they are to cause Henry to have full seisin without

delay of all that William, his father, held of the king in chief in his

bailiwick, and that was taken into the king’s hand by his order. Before

the justiciar and the bishops of Bath and Salisbury.

10/84 (28 January 1226)

For Henry of Hastings . It is written in the same manner to the sheriffs of Shropshire, Bedfordshire, Norfolk and Suffolk, excepting security and with the addition, ‘having received the letters of the sheriff of Warwickshire and Leicestershire

testifying that he had received security for rendering the aforesaid 50

m. to the king at the terms that the king has given him, they are to

cause him to have full seisin etc. as above’. Before the same.

- A fee

of the honour of Clare in Suffolk, in 1242 (Fees "919", which should read 918). Vol.II, page 918: "Alicia de Hauvill' tenet dimidium feodum de

Henrico de Hasting', et Henricus de Clare". Again this makes sense.

More questionably, Keats-Rohan notes that in 1242 William de Hastings

held one fee in Eaton in Berkshire (Fees Vol.II, 844), and associates this

man with the dispensator.

For William de Hastings, the son of Hugh, all the suggestions about future generations raise interesting questions:

- In 1235/6, says Keats-Rohan, the two and a half fees of William of Hastings in Tormarton,

'Suthrop' and 'Stawell' were held by the wife of Osbert Giffard, the

wife of William of Hastings and Geoffrey Martel (Fees, 438). This is in Gloucestershire, and again clearly the family of Eaton in Berkshire.

- In 1242

Henry de Hastings held one fee at Congerstone, Leicestershire, of Earl

Ferrers (Fees, 946). "In Cungeston' j. feodum quod Robertus Mutun' tenet de Henrico de Hasteng', et ipse de eodem comite."

The question this raises is how Keats-Rohan maintains a distinction

between this Henry and the one mentioned above in the Fine Rolls quoted

above. The heir of William de Hastings held lands not only in

Warwickshire and Leicestershire, but also Shropshire, Bedfordshire,

Norfolk and Suffolk.

- Keats-Rohan points out that a Henry de Hastings, son of William, occurs in a charter estimated to be from the late twelfth century, regarding a grant in Odstone, Leicestershire. Citation is to Stenton, Danelaw 463. If I understand correctly this dating estimation is being used to suggest that perhaps

this Henry son of William is not the one well-known from after 1226.

(Finding the name of a father of any Hastings in the difficult

generation at the end of the 12th century would be very useful, as will become clear below.) The

witness list will be discussed below and compared to other lists in

order to try to estimate when it was made.

This

brings us to an important point because this Henry in 1242 is certainly the same Henry who Keats-Rohan

suggests also as a descendant of the supposedly different William de

Hastings, the "dispensator". As seen, he inherited in 1226 after the

death of his father who was named William. This was in all the

counties where "both" the Williams mentioned by Keats-Rohan were most

certainly identified. Henry, and presumably his father William, were successors to "both"

the Williams thriving in 1166.

Interestingly,

the new William's contemporary in the Hastings

Eaton honour in Berkshire, had the same name, William de Hastings, and

died at about the same time. But his heir was under-age unlike Henry,

and the two families are quite easy to distinguish from that point on.

They held lands in different counties. Again

we can refer to the Fine Rolls.

8/79 (29 February 1224)

29

Feb. Marlborough. The fine of Osbert Gifford. Osbert Gifford has made

fine with the king by 200 m. for having custody of the land and heir of

William of Hastings , with the marriage of the heir of the same

William. Order to the sheriffs of Berkshire , Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire to cause him to have full seisin of all lands formerly of William in their bailiwicks.

11/197 (18 April 1227)

For

Osbert Gifford. The king has granted to Osbert Gifford that he may

render the �20 which he ought to have paid at Easter in the eleventh

year of the fine that he made with him for having the custody of the

land and heir of William of Hastings at St. John the Baptist in the

same year. Order to the sheriff of Berkshire to permit him to have

respite until that term.

13/276 (02 September 1229)

2

Sept. Windsor. Concerning the debt that Osbert Gifford owed to the

king. The king has granted to H. bishop of Rochester, Henry of Walpole

, Isabella de Friville and Matilda Gifford, sister of Osbert Gifford ,

executors of the testament of the same Osbert, that, of the �50 and

half a mark which still remains of the fine that Osbert made with the

king for having the custody of the land and heir of William of Hastings

, with the marriage of the same heir, they may render �20 per annum to

the king for Osbert at the same terms at the Exchequer at which he was

bound to pay them to the king. Order to the barons of the Exchequer to

cause this to be done and enrolled thus.

To quote the Victoria County History for Eaton Hastings,

"The heir in question was apparently the William de Hastings, who was

tenant in about 1240. He died in 1278, leaving a daughter and heir

Joan, then the wife of Sir Benedict de Blakenham". (William,

although he died a similar time to the father of Henry, appears to

have been significantly younger than his contemporary. Until 1212, there was a John de Hastings associated with these lands.)

To show which manors were inherited together and which were not, we can also refer again to the second volume of the Book of Fees

("Testa de Neville"), focusing only upon those mentioned by Keats-Rohan

as evidence. This was in 1242, long after the Fine Rolls inheritances

described above:

Gloucestershire, which Keats-Rohan allocates to the son of Hugh:

- p.819 in a Gascon Scutage list for Cirencestre (Gloucestershire): "De Christiana de Mutton' de dimidio feodo militis in Torinton' de feodo Willelmi de Hastinges, xx.s"

- Also on p.819 in Gloucestershire: "De Galfrido Martel pro dimidio feodo militis in Stawell' de feodo Willelmi de Hasting', xx.s."

Oxfordshire, which Keats-Rohan allocates to the dispensator:- p.822 in Bampton hundred in Oxfordshire: "Westwell', Eleford', Alwaldesberi. Willelmus de Hatinges tenet unum feodum militis et dimidium in capite de rege".

- p.841 in Oxfordshire: "Willelmus

de Hasting' tenet feodum unius militis et dimidii in Westwell', Eleford

et in Alewaldebur' in capite de rege. Willelmus de Hasting'. In rotulo".

Berkshire, also allocated by Keats-Rohan to the dispensator:- p.844 in Berkshire: "Willelmus de Hastinges in Eton' j. feodum".

- p.847 "Willelmus de Hastinges in Eton' j. feodum quod tenet de domino rege in capite."

- p.857 "Willelmus de Hastinges in Eton' unum feodum quod tenet de domino rege in capite. t. Habet respectum in Glouc."

East Anglia and Bedfordshire, where William the dapifer had definitely been, we find Henry in the same places:

- p.870 "Senescalli

Bluham. Henricus de Hastinges tenet v. hydas de libertate Sancti

Edmundi et ij. hydas Kenemundewyk de eadem libertate; non solebat dare

quia proprium hoc est senescalli."

- p.913 "Henricus de Hastinges tenet Aschele de domino rege per seriantiam panetrie."

- p.918 in Suffolk: "Alicia de Hauvill' tenet dimidium feodum de Henrico de Hasting', et Henricus de Clare."

Warwickshire and Leicestershire, where William the son of Hugh had definitely been, we also find Henry in the same places:- p.946 "In Cungeston' j.

feodum quod Robertus Mutun' tenet de Henrico de Hasteng', et

ipse de eodem comite."

- p.947 "In eadem villa de

Bramcot' tercia pars feodi quam Henricus de Hasteng' tenet

de eodem comite."

- p.948 "In Burthton' et

Schireford' j. feodum quod Henricus de Hasteng' tenet de

eodem comite."

- p.958 "In Manecestr' dimidium feodum quod Hugo de Manecestr' tenet de Henrico de Hasteng', et ipse de eodem comite."

Shropshire, although Keats-Rohan does not mention it, is also in mentioned

in the Fine Rolls above as connected to the inheritance of

Henry, which went together with Leicestershire, Warwickshire,

Norfolk and Suffolk. It came from the inheritance of the Banastre family there.

- p.964 "Henricus de Hastene quartam partem feodi in Eston' et Mosselawe."

This

Shropshire inheritance was actually held by his father's mother until a

few years before Henry inherited. Again from the Fine Rolls:

6/194 (17 June 1222)

17 June. Westminster. Shropshire.

To the sheriff of Shropshire . William of Hastings has made fine with

the king by 10 m. for his relief of two hides of land with

appurtenances in Aston, which Matilda Banaster, mother of the aforesaid

William, held of the king in chief and which fall to William by

inheritance, and the king has taken his homage for this. Order that,

having accepted security from him for rendering a moiety of the

aforesaid fine to the king at Michaelmas in the sixth year and the

other moiety at Easter next following in the seventh year, he is to

cause him to have full seisin without delay. Witness H. etc. By the

same and the king’s council.

In Compton, Surry in the Honour of Windsor, the Hastings family that lived there seems to have disappeared by 1242.

3. Jocelin of Brakelond

One

of the Keats-Rohan sources mentioned for William the dapifer and

steward is the precious contemporary account of Jocelin, who was in

the Abbey of Bury itself. Apart from mentioning the 5 fees, Jocelin also supplies Hastings genealogists

with a remarkable eye-witness account of something which could not have

been known from other records. It explains the

irregular way in which the dapifership was inherited in the generation

after the William who held this office in 1166, but it does not say what happened

between him dieing, which as we have seen might have been before 1170, and that moment in 1182. See page 106 of the recent Oxford paperback edition for one version of these events.

As

soon as Abbot Samson was elected and confirmed as the new abbot in

early 1182,

various people turned up with affairs needing attention from this

important lord. The one which Jocelin seems to have found most arresting was a young man named Henry de Hastings. (Clark interprets

it as 1 April and somehow extracts an exact age of 14 for Henry;

Rokewood, who edited a respected edition, gives 31 March.) He was not yet a

knight, and Abbot Samson considered him under-age and not yet

qualified.

Jocelin does not give the name of Henry's father, but he does say

that representing him to Samson was his uncle, named Thomas de

Hastings.

In another place, Jocelin had also mentioned in passing that the role of dapifer had

recently been performed by Robert de Flamvill. Apparently Thomas

himself was not only a knight, but he came with a

large number of knights, in a show of strength which Jocelin and the abbot found a

bit over-the-top. The most obvious assumption then, is that Thomas was the brother

of Henry's father. (He was probably the man who accounted for some

payments in the Pipe Rolls in 1175/6 and 1176/7, not only in East

Anglia, but also in Hereford "in Wales".)

Charter 150 in the Kalendar

of Samson, corresponds to Samson's first chapter meeting, and

unsurprisingly has both Thomas de Hastings and Robert de Flamvill as

first mentioned witnesses.

A Gilbert de Hastings then appears in charters from 1182 until later in

the 1180s, when he appears to have been replaced again by Robert de

Flamvill. Jocelin also mentions Gilbert. He says that Gilbert was accepted as a stand in while Henry was too young.

This record gives a starting point and helps geneaologists feel comfortable about the progession of this inheritance after this young Henry. According

to Clark, Pipe Roll records show that Henry received taxation

exemptions for going overseas, year 3 of Richard I, 1191/2 (so he was a

knight by then). He must have died soon after. (Moriarty believed this

meant he died either participating in the Third Crusade or soon after.) In

1194 a William de Hastings, the "new William" mentioned above, paid 100 marks as relief for the land and

serjeantry of his brother Henry, and another 100 to avoid going to

Normandy. Pipe Rolls 6

Richard I is cited by Eyton, Clark and Moriarty, all apparently

following Dugdale. Eyton adds that there is an accounting for one of

these fines the following year. He cites Madox p. 216, but it should be Vol.1, p.316. (That record states explicitly it is for the lands and serjeantry

- serjeantry being a less usual form of possession, so there is little room for misunderstanding who this is. It names the

brother Henry whose inheritance it is. It states that this was in

Norfolk or Suffolk. "Willelmus

de Haſtinges r c de C marcis, pro Relevio terr� a Serjanteria Henrici

fratris sui. Mag. Rot. 7. R. 1. Rot. 6. b. Norf. & Sudf.")

As

we approach the year 1200, a steady stream of records begins to appear

showing this new William, the brother of Henry, until we get to 1226

and his son, also named Henry, inherited.

But how do we prove the name of the father of this new William, with the

brother and son named Henry? (At least we can suggest his mother's

name, Maud de Banastre, as explained above, looking at Fine Roll evidence.)

And how do we prove that

this William inherited everything from only one William. Could

Keats-Rohan have been right to question this?

It is not unusual for a family to have several lines with important men

with the same name, and it is not unusual for the inheritance of

several lines to be united later in one heir.

4. Summary so far, and the importance of Dugdale's Glover collection citation

The

above exercise, which can be cross-checked using more Pipe Rolls and other records, seems to

bear out the common genealogical understanding that William de Hastings

in Eaton in Berkshire was a distinct person, while the son of Hugh in

the Midlands, and the steward in East Anglia were the same person.

But being cautious perhaps it is more correct to say that based on the above primary

records, these two Williams in the 1100s had the same successors in the

1200s: Henry and his brother William. Unless we can explain the exact route of that

succession before 1182 (when Samson was elected) there is some small room for doubt.

Investigation of secondary

sources shows that there is a source, already quoted on the first webpage, which explicitly equates the

"two" Williams and explains the line of succession in a simple way. The

problem is that this source is a 17th century secondary source, William

Dugdale's Baronage,

and although he describes information coming from original charters

which are now apparently lost, it is not clear anymore what exactly was

in those missing charters, and which information is Dugdale's interpretation. He does say that his evidence came from the collection of Robert Glover, a herald.

Dugdale appears to be the only source available for several things in the standard pedigree:

- The name of Hugh's father,

William. There would apparently be no hint of this from any other

record apart from Dugdale. Indeed Dugdale had

noticed a Walter de Hastings in the right time and place in the old records for the Abbey in Polesworth and in 1656 he named

him as the father of Hugh. Apparently what Dugdale saw in the charter

convinced him this Walter was not the father of Hugh. (Clark suggests Walter may be William's father. In a 1730 "corrected" version, made posthumously but based on Dugdale's own corrections, he makes William and Walter brothers.)

- The fact that Hugh's son William is the same as the dapifer/steward/"dispensator". This at least seems likely from known primary records, but that perhaps also makes it likely to be interpretation by Dugdale.

- The fact that Hugh's

son William was the Hastings who married Maud de Banestre, and was

father of William the father of Henry, mentioned above. This also seems likely from primary records, and so once again Dugdale's interpretation might be playing a role for this claim.

- The

fact that there was a marriage by one of the Williams to a daughter

named Margerie of one of the Roger Bigods who were Earls of Norfolk. (Dugdale gives a different version in his Hastings and Bigod

accounts. The Bigod version makes more sense, making this marriage that

of William, son of William de Hastings, not William son of

Hugh. Concerning which Roger, Dugdale says it was the one who died in

the 5th year of Henry III, 1219/20, and he also says that this Roger

had a step mother named Gundred.) There would apparently be no

clear hint of this from any

other record apart from Dugdale.2. (A hint of possible additional evidence of this marriage, also now perhaps lost might be found in Blomefield's article

on Gayton Thorpe. He says that this manor also came to the Hastings

family from the Bigod marriage, which he would have known of from

Dugdale. But this looks a bit like he might have been giving his own

interpretation of something likely. The branch of the Hastings who came

to hold this seem unlikely to have been descended from any proposed

Bigod marriage.)

It

has to be said, that Dugdale's account looks very likely, and many

genealogists will rightly say that the evidence we do have is so

perfectly consistent with it, that we can consider this proven within a

reasonable doubt.

But as has been reviewed, all record of William

who was thriving in 1166 seem to

stop by 1170. There are 12 years before we get to the moment

where uncle Thomas brought young Henry to see Abbot Samson. This is

just long enough for a young man to have grown up, but not

quite be considered ready to take up his office at

Bury, probably indicating that he was not 21. But on the

other hand there is also room for other scenarios. Could Henry have

been a nephew of William the dapifer for example?

In

any case the dapifer of 1166 almost certainly had brothers. Two apparent

brothers appear in Jocelin's account: Thomas de Hastings, named as an

uncle to young Henry, and Gilbert de Hastings, allowed to work as a

stand-in for Henry until he got older. But obviously neither of these

were the father of Henry, or they would have claimed the inheritance themselves.

In the

Pipe Rolls records of the 1170s, apart from Thomas who seems to have spent time in

Hereford, there is also a Phillip who appears suddenly accounting for

several hundreds in Norfolk in the Pipe Rolls of 1168/9. This Phillip

also appears in Eyton's Henry II itinerary, in 1175, after William ceased to appear. One charter was made in Marlborough, and the other in Valoignes, France. Cronne/David RRAN III, No. 823

is originally a 1153 charter made at Bridgnorth by Henry Duke of

Normandy, who had not yet become Henry II. One signatory is William de

Hastings, but it also mentions his brothers Phillip and Ralf. (The

people in the witness list might not all have been original witnesses

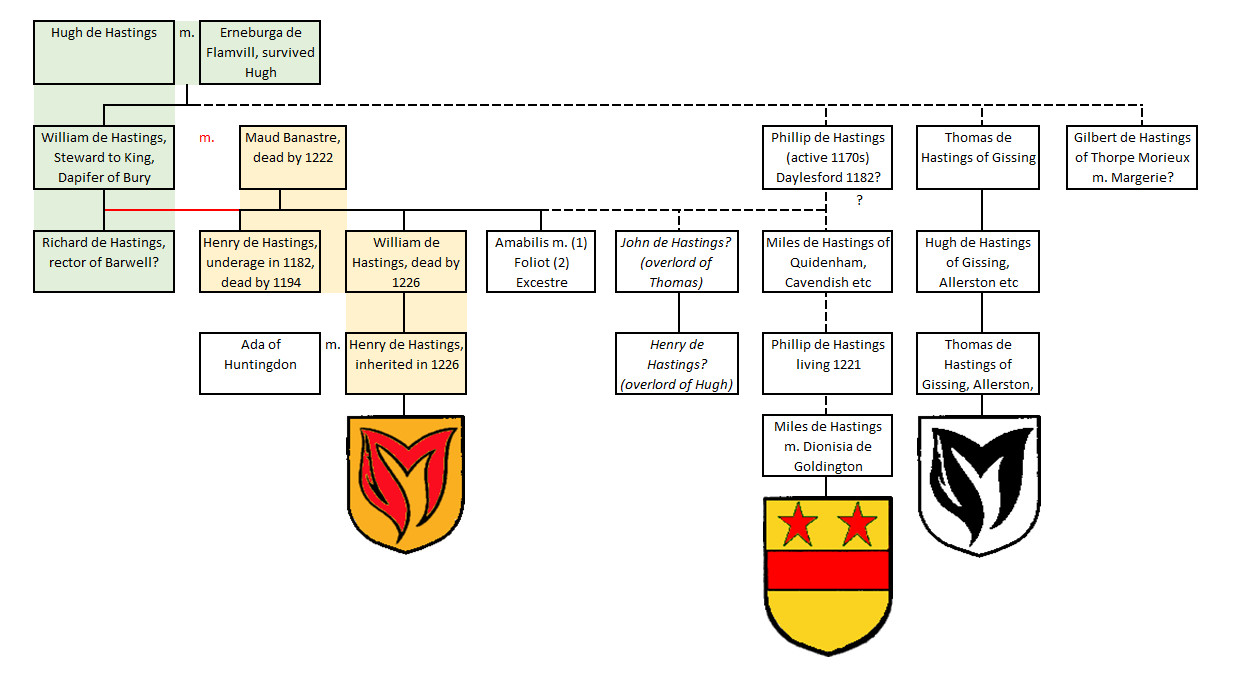

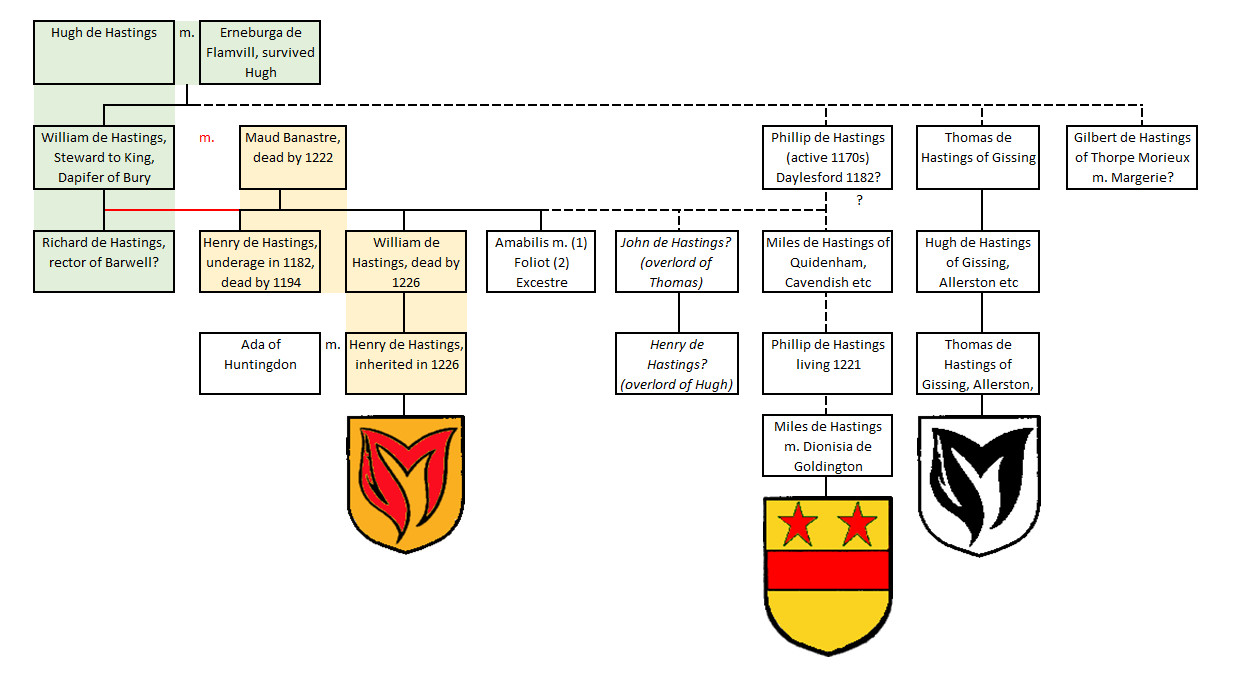

in 1153, because it appears to be a charter that was amalgamated later, making it unreliable.)pedigree 9. A simple descent from William the dispensator to Henry de Hastings

Investigation of the peculiar splitting of William de Hastings in Domesday Descendants

therefore leads to interesting questions. While Keats-Rohan's division of the

records into these "two" men seems questionable, it is also not simple

to prove that these are one person. The generally accepted family trees

which link this William to his successors are typically variations upon the following...

Notes for this pedigree:

- The top of the tree (Hugh, his wife Erneburga, their son William and his son Richard) has one clear medieval source: a Patent Roll inspeximus

of Richard II which states that

Erneburga made a grant of the Church of Barwell as the mother of William de Hastings, and

with the assent of Richard his son. (Query: Dugdale, citing this, makes this Richard the son

of Hugo, not William, and refers to him as the rector of Barwell. Did Dugdale read something else?)

In any case this charter was said to have been made in the time of

Henry II (1154-1187) in Northampton. Eyton, in his itinerary of

Henry II, mentions a Richard de Hastings that was a brother or nephew

of William de Hastings, and a cleric, in 1169.

Appearing frequently in these times is also a Richard de Hastings who

was a Templar and important functionary in church and state matters,

but Eyton gives them separate entries. Indeed in documents normal

clerics were not normally called Magisters like a master of the

Templars would be, and a master of the Templars would not be called a

mere cleric. (Moriarty wonders if the cleric nephew became a master Templar.)

- The last part of the main line in the pedigree (Henry, his father William, and his father's mother Maud de Banestre)

is also something which can be convincingly demonstrated from primary

records. The relatively quick succession of Fine Roll records, including Shropshire possessions from the Banestre family, is

already discussed above.

- A Thomas de Hastings is said to be the ancestor of the Earls of Huntingdon, and as Eyton mentions (p.138),

the "genealogists" say it is the uncle

mentioned by Jocelin of Brakelond in 1182. Blomefield notes a Quo Warranto

record of 1227 where one of Thomas's descendants claimed that his

right to Gissing and Tibbenham came to him from his ancestor

"William

de Hastyng", "of the fee of St. Edmund, in the time of Henry II. and

that he then peaceably enjoyed all these liberties, which were

confirmed to him by the charter of King Richard I. in the seventh year

of his reign" (1195/6). On the other hand, "ancestor" might be a translation of

antecessor, which can simply mean predecessor. I have followed the

genealogists based on the fact that Thomas seems to have been a knight

already in the 1170s and the

heir of Thomas, Hugh, was in his prime already in the 1190s, and dead

not long after 1200.

- Miles de Hastings. Under

Quidenham

Blomefield informs us that a man of this name was holding part of it

(Guidenham) by 1194, and another (Hockhams)

by 1199, it

having previously been held under Abbot Samson of Bury by Ernald

de Charneles. (A Charneles was an acting dapifer for Bury during this

period. Note that Jocelyn names Ernald as holding Quidenham around

1200, but with "parceners".) Miles also appears in Rye's Calendar: 1200/1201, Milo de Hastings of Quidenham. The name Miles de

Hastings is also associated with Cavendish in Suffolk. A charter in

David (ed. p.144) associates him with Elveden in Suffolk. Under Babergh

hundred he is also mentioned 3 times, twice specifically mentioning

Hochetone or Hoccetone (Hawkeden? Acton? Houghton in Cavendish?). In 1201, the Curia Regis rolls show he

was holding Hockington under William de Hastings, presumably the same

place. It seems to be either his son or grandson, also named Miles (and

apparently his father also), who married the heiress of Stoke

Goldington, Dionisia (Denise). They had a son Miles (d.1305; see IPM.) whose heir was his grandson Miles (d.1311, about 30 in 1305), son of Phillip de Hastings (d. 1282). Moston John Armstrong says the family also had Elesford (Yelford) in Oxfordshire and Dayslesford in Worcestershire. They apparently had their own arms as a family, without the Hastings/Flamvill "maunch" (damsel's sleeve). It

seems in Yelford the overlords were the Hastings family of Hastings

Eaton, and the family of Miles seems to begin with a Phillip in 1221

(so maybe the sequence in this family goes Miles, Phillip, Miles,

Miles, Miles (d.1305), Phillip, Miles (d.1311). Interestingly, Daylesford had been

held by Phillip de Haster in 1182.

- Gilbert

de Hastings. Known

from Jocelyn de Brakelond and other sources as a man who sometimes

stood in as dapifer of Bury. Probably an older relative of the brothers

Henry and William. He may be the

one who is found in these times in Thorpe Morieux in Sufffolk. This

place is often listed as simply Thorpe, and under Lancaster, because it

was part of the Honour of Lancaster. See Farrer's Lancashire Feudal

aids (p.28), the Lancashire Pipe Rolls, especially p.145, and the Red Book of the Exchequer Vol.I p.141, p.479, p.590.

In the Kalender of Samson he appears in the feudal survey of Cosford

half-hundred, which contained Thorpe (Davis p.57), holding 1 "sectam".

In his place in Thorpe, after about 1210, we find Margerie de Hastings,

perhaps a widow (Red Book p.570, Testa de Nevill p.224 ).

- Amabilis or Amabel, is said to be sister to William de Hastings. This is based on several small bits of evidence. In Richardson's words (Royal Ancestry

III p.245): (1) "About 1195-1205,

he conveyed a rent of �5 in Blunham, Bedfordshire to Richard Foliot, in

marriage with an un-named sister"; (2) "charter dated ?1200/1210 of

Amabilis de Hastings, mentions the mill she had in free marriage in

Blunham Bedfordshire, a Hastings family holding"; (3) The editor of the

Cartulary of Old Wardon "suggests that Amabel de Hastings (living

c.1200/1210), widow of Ralf de Exeter, mabe the same person as the

unnamed sister of William de Hastings, who married c.1195/1205 Richard

Foliot". (Ralf de Excestre's mother appears to have been a member of

the Hastings family of Little Easton.)

5. The charter evidence

To

try to tie up the missing link more convincingly, possibly the only

method is to look at charters concerning such things as grants of land.

Most of these do not have dates on them unfortunately. But in this

period, lords of a reasonable importance would often have a relatively

fixed "familia" of allied men,

often knights enfeoffed under them, who appeared in many such documents

as witnesses. Historians therefore sometimes try to date charters based

on which people do or do not appear. This is often very difficult for a

family like this who were not yet of a very high status. The families

under them are relatively unknown, even if some later became

well-known. Luckily though, the Hastings position as the dapifer of

Bury is well-documented, and the dapifers used lieutenants who were

often close relatives. Thus we can also compare to Bury documents.

There is a list of lieutenant dapifers for the

period of Abbot Samson, made by Davis (li).3. Samson ran Bury from 1182

until 1212, overlapping the reigns of Richard and John: - Robert

Flamvill is mentioned by Jocelin as being in the dapifer position before Henry

and his uncle Thomas appeared in early 1182, and he also

appears in charters of the previous Abbot, Hugh (Douglas ed., 153, 154).

He is the first known stand-in dapifer for the Hastings family. Someone

with the

same name, returned to duty between 1188 and 1198. It is worth noting

that the mother of William de Hastings the son of Hugh, was named

Erneburga de Flamvill. The Flamvills were connected to the Hastings for

generations, and this Flamvill family appears to be the one who lived

in the manor of Aston Flamville in Leicestershire, with the Hastings as their overlords.

- Gilbert

de Hastings

is discussed above under the pedigree. He was assigned as stand-in

dapifer at Bury in 1182 according to Jocelyn. As mentioned above he

must have been older than the brothers Henry and William, and his

surname seems to indicate he is a relative, possibly another uncle - a

younger brother of Thomas for example. He appears in one Samson charter (56) which is estimated to

be earlier than 1188. As mentioned above, he seems to have died about 1210, which makes him useful for our purpose.

- William

de Cherneles appears in records as dapifer (seneschal) in

one charter (number 80 in Davis, p.122) approximately dated to 1201-5, involving

Troston. Davis also notes that he appears as seneschal of the Abbot's lands

in the Curia Regis rolls i.457, dated to 1201. The surname was also found in Leicestershire (Shearsby, Snarston), associated with the Hastings. The name William was used many times.

- Miles de Hastings is mentioned above in the pedigree. He appears as lieutenant dapifer once, in the period 1200-1211. Under Quidenham

Blomefield informs us that Miles de Hastings held part already in 1194,

and took over more by 1199 which had been held in 1196 by

Ernald

de Charneles. (Same surname as Cherneles.)

- William de Hastings himself, or someone with his name, appears in a couple of charters as dapifer, around 1205-6.

- William of Cretingham appears in many charters as dapifer of Bury in the period of approximately 1206-1212.

A William de Cretingham appears in a dated charter, 29 June 1188 concerning land in Cretingham, and there seem to be earlier sightings in the time of Abbot Hugo. A series of ancient deeds thought to be 12th century show that his heir was Arnold de Coleville. A person of the same name appears in Hardley with a Henry de Hastings in the 8th year of King John (1206/7). Gretingham was one of

the holdings that later Hastings Earls held under Clare, and this

surname, with various spellings, appears often in Hastings witness

lists. Nicholas de Gretingham held the manor in the time of Henry III.

A challenging charter from Gissing.

A charter exists, wherein the manor of Gissing, known to be a Hastings sub-enfeoffment to a cadet branch, was first granted by John,

and confirmed by his son Henry. In the pedigree above there are two better-known Henrys who were overlords of these lands, but both had father's named William. It is hard to ignore the charter given the lack of strong

primary evidence for some of the steps in the standard pedigree. It is

one of the few charters that clearly mentions the name of a father

of a Hastings in this period and in this family, and this is not

just any Hastings, but one who had a quite well-known branch as a

tenant under him. To make it match with the standard pedigree, it is

generally assumed that John was himself also enfeoffed under a still

more senior Hastings overlord - one of the two Williams or one of their

two sons named Henry. But no overlord is mentioned and

it seems remarkable for what seems to be an important grant, that there

is not even a William among the witnesses. (It would be irregular to

not have him

present as a witness in such a charter, and not even mentioned,

although perhaps he was overseas and the family had clear enough

understandings?) There seems to be no other evidence anywhere for the

existence of such a 3 level Hastings lordship, nor for either John, or

his son Henry.

Because

of this one charter, there appears to be an obvious "Devil's Advocate"

hypothesis to make, in order to test the standard pedigree:

- Could

it be that the father of Henry (presented in Bury in 1182) and William

(took over from his brother), was named John, not William? He would also be the husband of their mother Maud de Banastre.

- If

he existed, such a John would have been in the line to inherit from

the previous William (alive in 1166) if he had no child able to inherit.

Most obviously, he might be a younger brother or a son. He would then

have

died before William, or at a similar time, as there is no record of him inheriting. His

children would have been born before the death of William, as in

the standard pedigree.

- If we reject this proposal, then we still have to accept something

similarly awkward, which is that not only this John but also his son

Henry were important enough to be overlords of other Hastings for two

generations, and yet appear in no other records.

Gissing was

undoubtedly a manor which went with the dapifership. This charter was

mentioned by Dugdale, Blomefield, Clark, Moriarty and

others. It has been most recently been reproduced in the Report on the Manuscripts of the late Reginald Rawdon Hastings, Esq. of the Manor House, Ashby De La Zouch

by Francis Bickley (Historical Manuscripts Commission 78) p.206. The

charter has no date on it, but it has a useful list of witnesses.

In it, Henry son of John de Hasting

granted Gissing to Hugh son of Thomas de Hasting. That Gissing had been

granted as a sub-enfeoffment to Thomas (probably uncle Thomas in 1182)

and that this Thomas had a son named Hugh, who also had a son Thomas, matches perfectly well with

everything known about what would become a famous Hastings family in

its own right.

The editors propose the date must be in the

time of King John or Richard I, which makes sense, because the

witnesses are a striking match for the Hastings family of that period: Miles de Hastig', Robert de Flammville, Gilbert de Hastig', William de

Gertigham, Henry Sarac', William de Flammville, Adam de Corneburc,

Walter de Manto', Bernard Burd', John de Baucam, Adam son of Michael,

Thomas de Richebur', John de Hou'.

To compare to the above list, the first four

witnesses in the Gissing charter correspond to known acting dapifers of Bury in the period of Samson.

The Devil's advocate proposal does give

a chronological problem.

If Henry the son of John in the Gissing charter is to be equated with

young Henry of 1182, then we know that Henry was dead by 1194. The

charter would then demand us to believe that Hugh de Hastings of

Gissing had already replaced his father Thomas by that time. But Thomas

appears to have outlived his nephew Henry. A Thomas de Hastings appears in Walter

Rye's Calendar of old Norwich Feet of Fines 1195/6: Thomas de Hasting in Frense, Tistehall, and Gissing.

In

fact, the period when the first Hugh of Gissing, son of Thomas, was

holding his family manors may have only been a few years. And it was some time

before the name Hugh appeared in the family again, so we

would expect different witnesses if this was a later Hugh.

So at least we can say that

the Devil's advocate proposal is itself not very satisfying. One way or

another, all proposals for explaining the charter seem to require us to

invent missing people who do not appear in other evidence. We can solve

the problem by proposing an extra Thomas, instead of an extra Henry for

example.

Reassuring charters

To

test the standard theory and this counter proposal then, we should

compare this list to the list of witnesses given for the charter

Keats-Rohan mentions for Henry the son of William: charter 463 in Stenton (1920): Henricus de Hastinges filius Willelmi de Hastings making a grant of all his lands in Odstone to Maheo de Charun filio Willelmi de Charun.

Keats-Rohan correctly points to a conventional dating of this charter

as before 1200, which makes this charter good possible evidence to help

confirm the standard pedigree.

Witnesses:

Thoma de Hastings, Willelmo de Hastings, Hogone de Nouilla, Ricardo

de Hastinges, Radulfo Execestre, Rodberto de Flamuilla, Ricardo de

Beuel', Gilleberto de Hastinges, Milone de Hastings, Willelmo de

Gretingeham, Hugone de Hastings, Oliuero Sarazin, Rodberto Sarazin,

Elya de Barewelle, Hugone de Herdebi, Baldewino de Charun, magistro

Rodberto de Barewelle.

The

coincidence of witnesses between the two charters can not be ignored,

so we are looking at the same family in a similar period. But

this time the father of Henry is named as William,

which would fit

standard genealogies better than John. (In fact the standard genealogies

say there were two Henrys who were sons of Williams.) There is also not

only a William this time but both a Thomas and a Hugo de Hastings.

The

dating of this charter is obviously important for this discussion. If

it was before 1195, when young Henry died, it would be a strong

argument for the standard pedigree.

- The fact that William de Hastings appears, but

not as grantor, is worth noting. It would for example fit a situation

where he was a family member, but not the one with rights over this

land in Odstone. Being one of the first witnesses would be typical if

he was possibly considered to be in line to inherit. But it seems (see

above) that Odstone was a small holding, held by the main line. So this

would fit the proposal that he is here not the family leader, despite being in

line to inherit.

- The unusual surname "Sarazin" is asociated with

the Hastings familia in this period and in particular with Shakerstone,

near Odstone. On the Medieval Genealogy list it has been pointed out that this family also married the Flamvilles. A Prosopon Newsletter article

by John S. Moore discusses this family. (He assumes that the name means Saracen). It shows that a family at that time is

known to have had a connection to Odstone, and both the Hastings and

the Flamvilles families. Also see the discussion of the Sarazins here, showing how they became the modern Sarsons. The names Robert and Oliver may have been used more than once.

- If Ralf de Excestre

is the brother-in-law of William de Hastings (mentioned above and on

the first webpage) then it appears he would not have been married

to Amabilis yet in 1195, but on the other hand he would also have died

around 1200, and his family interests were linked to William's

dapifership inheritance before 1195, as explained on the first webpage.

- Like Ralf de Excestre, the name Richard de Hastings

comes up often in charters associated with Wix and the Hastings family

of Little Easton. One of them was a brother of William fitz Robert and

that William died 1161/2 (Ancient Deed A.13881).

It is hard to date all sightings of Richards, and there may have been

several, but the name is strongly associated with the time of

Henry II, whose reign ended 1189.

- If this Hugo and Thomas de Hastings

are both from the family of Gissing, then we should keep in mind that

Hugh's son and heir was also named Thomas, not only his father. But the

sequence of the witnesses, putting Thomas first, seems to indicate that

he is a very senior Hastings, while Hugo is not.

- Hugh de Nouilla looks like he might be Hugh de Neville, chief forester and constable of Marlborough Castle. According to VCH Wiltshire, "Richard I committed Marlborough in 1194 to Hugh de Neville who remained keeper under John". But Wikipedia says

he was already active earlier, "a member of the household of Prince

Richard, later Richard I, and also served Richard's father, King Henry

II at the end of Henry's reign, administering two baronies for the

king". He married a Cornhill and had a connection to Essex so he

would perhaps have been a relative also of the Hastings family of

Little Easton. Standard reference works such as ODNB, and Douglas Richardson's Royal Ancestry

report that he did not die until "shortly

before 21 July 1234". Henry certainly went with King Richard on

crusade, apparently like young Henry de Hastings who was presented at

Bury in 1182.

Another similar, and possibly related charter appears in the

Hastings Manuscripts, page 43. This time Henry de Hastinges, son of

William de Hastinges, grants the mill of Nailstone called "Erlesmulne"

to William de Oddeston, son of Ellis de Oddeston. Witnesses: Richard de Harcurt, William de Dustone, Hugh de Neuville, William de Carnelle, Adam de Hertewelle, William de Meulinge, Alexander, parson of Burbach, William Venator of "Elleslege" and many others.

If the case is strong that this Henry son of William is not a later

generation, then a third awkward possibility arises. Could there simply

have been a

mis-transcription by a scribe, who for some reason simply wrote John

instead

of William on the Gissing charter?

Looking for extra Johns and Henrys.

There is evidence of a John de Hastings being an important member of this

families in the first years after 1200. Even though that was too late

to be a father of young Henry in 1182, it is not too late for the

witness list more generally and might still be relevant:

- Concerning Ashill, Round noted

that at the first clear mention of the Ashill serjeantry in 1204/5 it is John, not William: "Johannes de Hastings tenet manerium quod vocatur

le Uppe Hall in Ashele, in

capite de domino Rege, per serjantiam essendi panetarius domini Regis"

(Rot. Fin. 6 John, m. 28 dors). But only a few years later William de

Hastings is in Ashill as King's servant: "Willelmus de Hasting' tenet

x libratas terre in Asle per serjantiam scilicet existendi despensarius

in Despensa Domini Regis" (Testa de Nevill p. 294 in older edition. Newer edition p.132

under 1212). As Rosie Bevan points out to me, there is evidence that

William had lost control of his properties in the period when this John

held the estate, due to debt.

- Henry who inherited in 1226 was apparently

also heir to a John de Hastings, who, like his father, had been active

in the time of King John (to whom he still owed money for the Ireland

campaigns of that time). (This of course implies that this John had no

son named Henry, at least not still alive in 1226.)

- Around 1200 King John granted

Aylsham in Norfolk, previously a possession of the King, to Bury. One

of his tenants in chief was John de Hastings. Blomefield, also mentions him under Aylsham,

and a man of the same name at the same time was also instituted as

rector there. He also indicates that there are later signs of a

continuation of this family under Bintre-Hastings, and Irmingland for example. Under Tutington

he mentions evidence that a Henry son of Robert de Hastings of

Aylsham died in 1284. (If John was the same as the rector though, then

it seems unlikely that the continuation of the line was from a son.)

A Henry de Hastings appears

as a witness in Hardley, Norfolk, in the 8th year of King John (1206/7)

and also appears to be a relative because he is in the correct area,

and together with a man named William de Gretingham..

This

gives us a possible retort to the Devil's advocate question. Perhaps

there are signs after all of the right John and the right Henry. We know that in the period of

King John, William de Hastings had his lands taken from him both for

debt reasons, and also because William was involved in rebellion. Each

time, he seemed to resolve it eventually. The case of Ashill alerts us

to the possibility that William was occasionally able to keep Hastings

control in a manor by deferring to other trusted family members. Might whatever happened

at Ashill also have happened at Gissing, something irregular?

6. List: all the likely possessions of the family

Trying to unite, if possible, all separate lines of evidence concerning what is traditionally supposed to be one William

de Hastings in this period, the following seem important to the story. This can then be compared to various strands of evidence.

- William was already

dispensator to the King at the time of inheriting this from his uncle,

and this service was (at least in later generations) given in return

for the manor of Uphall manor in Ashill in Norfolk (sometimes written Ashele

etc, in records from this time.)

- And he held the dapifer's lands of Lidgate, Blunham, Herling, Tibbenham and Gissing. From Dodwell's Charter 8 we also would expect that William might have inherited lands in Purleigh, Northey and Otley

(Suffolk), which Ralf his uncle had granted to the nuns in Wix. In

particular, while Purleigh and Northey were passed down from Maurice

the previous dapifer, the lands in Otley were something he added to the grant.

- He could

be expected to have lands in Leicestershire,

Warwickshire, Buckinghamshire and Middlesex where Hugh his father had paid fine to

the king for his wife's inheritance from the Flamville family, a branch of whom

remained in Aston-Flamvill (Leicestershire) as his under-tenants. The Flamville inheritance named by the king included Burbage,

Barwell, Birdingbury, Sketchley, Ashton, Stapleton, houses in Coventry,

and a croft in Willey.

- But he could also have other

possessions from the Hugh's own family, with the most frequently repeated suggestions being Fillongley in Warwickshire (under Marmion). Congerstone and Odstone, both in Shackerstone, plus nearby Nailstone in Leicestershire, and Oldbury (or at least Mancetter) in Warwickshire also seem likely (see Dugdale's Warwickshire).

- William is supposed by Eyton to have married

Maud Banester. Eyton focuses upon

evidence of an inheritance dispute between Mathilda and her sister

Margery, both daughters of Thurstan Banaster. From the Banaster family

it appears that the the Hastings inherited Munslow and the village of Aston near Munslow, both in Shropshire.

- According

to Dugdale, again citing the Glover collection, a William de Hastings

in this period married Margery Bigod, daughter of Roger Bigod. It is

generally assumed,

for example by Eyton and Clark, that this must be the son of the

William who married Maud Banestre. Dugdale however never mentioned the

Banestres and under Hastings (p.574) placed this marriage in the place

of Maud Banastre, though under Bigod he agrees with Eyton and Clark.

Dugdale specified that this Margery

brought the manor of Little Bradley in Suffolk

to the marriage, at least for her life. For all these things he names

his source as the Glover collection. An earlier source sometimes given

for this marriage is Milles The Catalogue of Honour

(1610) p.503. But Milles was nephew of Robert Glover and so he apparently

used the same sources as Dugdale. Clark specifically says that Margery

died 31 March 1237,

but only names Milles, Dugdale and Eyton as sources. Blomefield in his article on Gayton Thorpe in Norfolk says that this manor also came to the Hastings family from the Bigod marriage.

7. Notes for Thomas de Hastings.

- There

are other theories about the exact relationship of Thomas to

his

Hastings kin, apart from the suggestion above where Thomas is a brother to William the dapifer (alive 1166).

- Blomefield

(and Moriarty apparently following him) proposes that John (who granted

Gissing to Thomas) and Thomas are both younger sons of William the

dapifer (alive 1166).

- Consistent with this, Blomefield reports that in a Quo Warranto

case in 1227, a later Thomas pleaded that William de Hastyng, his

ancestor (or predecessor?), was

seized of Gissing, Tibbenham, and other manors he now held, of the fee

of St. Edmund, in the time of Henry II and that he then peaceably

enjoyed all these liberties, which were confirmed to him by the charter

of King Richard I in the seventh year of his reign, 1195. However this

record has not been possible to trace, and putting Thomas in this

generation would mean he could not have been the uncle in 1182 or

he would be younger

than his nephews.

- Eyton (p.138)

suggests that "the genealogists" say that Thomas is the son Erneburga

de Flamville, which make him the same generation as the dapifer of

1166. This seems the most common proposal (and as Rosie Bevan points

out to me, it would fit with the tradition of naming one's first son

after one's father).

- Clark has him still another generation further back, as a brother to Ralf and Hugh, but also admits to doubts about this.

- Blomefield

(and Moriarty) say the first Thomas de Hastings of Gissing

was dead by 1194/5. However, a Thomas de Hastings appears in Walter

Rye's Calendar of old Norwich Feet of Fines 1195/6: Thomas de Hasting

in Frense, Tistehall, and Gissing.

- His son Hugh is generally considered to have been

dead by 1203 and was in his prime in the 1190s.

- Blomefield

connects the fate of the Hastings manor in West Herling to that of

Gissing, but saying that "Hugh, son of William de Hastyngs, Steward to

King Henry I. infeoffed Sir William de Hakeford, Knt. who held it also

at one fee, paying 18d. every twenty weeks, to the Abbot, to the ward

of Norwich castle, which tenure continued till after 1630". Presumably

Blomefield saw a record, but it would be interesting to know how he

dated it to Henry I. Perhaps it was later and he weas guessing.

- The Hastings manor in Tibbenham is also treated by Blomefield as if it was inherited together with Gissing.

However not many details seem available between 1200 (William de

Hastings mentioned by Jocelin de Brakelond) and the later Earls of

Pembroke who were overlords here.

Other Hastings families active in the 12th century

A reference list:

- The

Hasteng family of Hastings Leamington in

Warwickshire. In this period, the spellings were not consistently

different from the Hastings family, and they lived in a very similar

area and shared a landlord.

- The "Hastings or Eton" family of Eaton Hastings

in Berkshire.

- The Hastings family found in Sussex and Essex in Domesday. See the second "Willelm de Hastings" in DD. They became heirs of Waleran. Also see Clark, and Round.

- The family of "Ingelran de Ou" (DP),

probable sheriff of Hastings itself, whom Keats-Rohan says probably had

descendents with the Hastings surname mentioned in the cartulary of

Ramsey, and possessing land in Huntingdonshire, for example in Gidding

and Liddington. Keats-Rohan says "He was succeeded in Huntingdonshire by Drogo of Hastings (q.v.) father of Helias and Ralph" (DD, p.280).

Notes.

1. Actually,

in later generations his family was described as having the office of

"naperie". Round's article on the King's serjeants (see Bibliography)

tries to make sense of these things, and expresses frustration at the

confusions people have. But it seems that not only could a family's

inherited serjeantries evolve, and be disputed, but also talented

individuals might have expanded duties beyond those they had by

inherited right. William was called a royal dispensator, and this was

apparently not inherited, nor passed on. His uncle Ralf, from whom he

inherited at least one office, was better known from another quite

different office in his own lifetime, that of dapifer to the queen.

Possibly William and/or his uncle Ralf showed some talent in management.

2. Online, Douglas Richardson has discussed this:

"Margaret le Bigod, is alleged by Dugdale to have had the manor of

Little Bradley, Suffolk in marriage, which might well be true.

However, I don't find any of the later male members of the Hastings

family dealing with this manor, so the manor was probably passed in

marriage to one of the later Hastings women in this time period." He

also found evidence that the Bigod family had at least held Great

Bradley (E 40/3775. Grant by William Bygod, lord of Great Bradley near

St. Edmund's). Also, for Bradley generally, Katharine Keats-Rohan's

newsletter, Prosopon, No. 10 (1999), pg. 3: "Adeliza Bigod was

addressed in writs of Henry I and Stephen concerning tithes at Bradley,

Suffolk: Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum, II, nos 1485, 1495; III, no.

82." Little Bradley does seem to appear in the Inquisition Post Mortem of the first John de Hastings. Dugdale's

position that Margerie Bigod first married William Cumin and remarried

William de Hastings not too long before 1216, is not tenable. But there

was a William de Hastings who had such a marriage. Round wrote this up,

and noted that this Margerie was an heiress of the Giffard family of

Font Hill, not a Bigod. This William de Hastings must have been dead

long before the dapifer, according to the inheritance successions noted

by Round. Furthermore, Henry de Hastings, the Bury dapifer's heir was

an adult and able to take up in inheritance in January 1226, only 10

years later. A less well-known claim is found

in a 19th century article on the Bigods, saying that Margerie first

married a William de Camville, before marrying William de Hastings, but

the source is not stated.

3. Douglas, the editor of the Bury charters, cites L. J. Redstone, in the Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology, Vol.15, pt.2, pp.200ff as an authority on the stewardship of the Hastings.

A later article which cover this subject is "The Stewardship of the

Liberty of the Eight and a Half of the Hundreds" by Angela Green, Vol.30, pt.3 (1966).

These articles show the Hastings family held on to the dapifership for

centuries, but developed a tradition of having deputies who performed

the function for them.

Key Sources.

Brooke, C. N. L. (1960) "Episcopal Charters for Wix Priory", A Medieval Miscellany for Doris Mary Stenton.

Clarence Smith J. A., (1966), "Hastings of Little Easton (part 1)", Transactions

of the Essex Archaeological Society. Vol. 2, Part 1.

Clarence Smith, J. A. (1968),

"Hastings of Little Easton (concluded)", Transactions

of the Essex Archaeological Society. Vol. 2, Part 2.

Clark, G. T. C. (1869), "The Rise and Race of Hastings" (in 3

parts), Archaeological

Journal, Vol. 26. [archive.org

link]

Davis, R. H. C. (1954), The Kalendar of Abbot Samson of Bury St. Edmunds and Related Documents.

Dodwell, B. (1960) "Some Charters Relating to the Honour of Bacton", A Medieval Miscellany for Doris Mary Stenton.

Douglas, D. C. (1932), Feudal

documents from the abbey of Bury St. Edmunds. [Hathitrust

link]

Dugdale, W. (1656), Antiquities of Warwickshire. [archive.org links for p.741, p.774,

and p.778]

Dugdale, W. (1675-6), The baronage of England, [link for Bigod and Hastings; there is also a separate account for the Hastings line of Gissing and Allerston]

Dugdale, W. (1730), Antiquities of Warwickshire ("corrected" version made posthumously based on Dugdale's own corrections). [vol II on google books, see p.1024ff.]

Eyton, R. W. (1857), Antiquities

of Shropshire, Vol. 5. [google

books link]

Eyton, R. W. (1878), Court, household and itinerary of King Henry II. [archive.org link]

Green, A. (1966), "The Stewardship of the

Liberty of the Eight and a Half of the Hundreds", Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology, Vol.30, Part 3. [Suffolk Institute link]

Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (1999), Domesday

People: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents,

1066-1166. Volume I: Domesday Book.

Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (2000), "Additions and Corrections to Sanders’s

Baronies", Prosopon

Newsletter. [own

link]

Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (2001), Domesday

Descendants: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents,

1066-1166. Volume II: Pipe Rolls to Cartae Baronum.

Landon, L. (1928), "The Barony of Little Easton and the Family of Hastings", Transactions

of the Essex Archaeological Society. New Series, Vol. 19,

Part 3.

Moriarty, G. A. (1942), "The origin of the Hastings", New

England Historical Genealogical Register,

Vol.96.

Moriarty, G. A. (1947),

"Hastings, barons of Little Eston, C. Essex, England", New

England Historical Genealogical Register, Vol.101.

Redstone L. J. (1914), "The Liberty of St. Edmund", Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology, Vol.15, Part 2. [Suffolk Institute link]

Rokewood, J. G. (1840), Chronica

Jocelini de Brakelonda, Camden (Latin edition). [google

books link; example of an English edition online at

archive.org here]

Round, J. H. (1902), "Castle Guard", Archaeological

Journal, Vol. 59, 2nd series, Vol. 9. [archive.org

link]

Round, J. H. (1902), "The Origin of the Fitzgeralds I", The

Ancestor, Number 1. [archive.org

link]

Round, J. H. (1902), "The Origin of the Fitzgeralds II", The

Ancestor, Number 2. [archive.org

link]

Round, J. H. (1903), "The Origin of the Carews", The

Ancestor, Number 5. [archive.org

link]

Round, J. H. (1903), "The Manor of

Colne Engaine", Transactions of the Essex

Archaeological Society. New Series, Vol. 8. [archive.org

link]

Round, J. H. (1911), The