Hastings families of the 12th century: what is known and what

is not

Summary . This two-part article is written by me, Andrew Lancaster, begun

in 2014 with

the hope of assisting genealogical and historical research. But to make

sure it

does not simply add to confusion, fellow researchers are asked to

record

it as a source if they find something new (including new ways

of

putting things) that they wish to use,

and to include this information when passing on that information to

others (as should be done with all sources). Please also note that

because it is intended to be improved when possible, the text will

change over time, and therefore you should consider recording the date

of accessing it in

your notes. Keeping in mind the aim of informing, rather than

confusing, anyone with constructive feedback and suggestions is

also requested to

contact

me.

To jump to the second webpage,

click here.

It goes into more detail about the Hastings family of Fillongley,

Warwickshire and Ashill, Norfolk, hereditary dapifers of Bury and

holders of the royal office of "naperie". But they are already

discussed below, in part I also.

I

have had helpful correspondence, but one person in particular who

should be thanked is Rosie Bevan, whose experience and knowledge helped

me improve both webpages.

Aims and methods.

The

noble English-based Hastings families of the 13th to 15th centuries are

much studied and discussed, but any survey of genealogical

discussions from the first printed books on such matters, right

through until today's internet, shows that the question of their

origins

in the 11th and 12th

centuries is a long-term source of confusion

and frustration.

Progress, though

inevitably slow in such matters, has been real in this case,

but the very intensity of published discussion (now exponentially

increased by the internet) creates its own confusions. Some of the most

respected published authorities writing in the modern era disagree

about basic points, and students of this family therefore find it hard

to

ascertain what is known, and what is not. It therefore

seemed worthwhile to

attempt

to make a new summary of the best evidence and arguments available.

Concerning sourcing for this webpage, there are short in-line

references

to standard works, and to the small number of key works in the

bibliography. (Any authors or pages numbers appearing without explanation should be traceable there.) There are also some

footnotes where detail would distract. But given

the aims described

above I have tried to be thorough about most sourcing discussions in

the body of the text. Apart from simply trying to explain the latest

ideas and what is most likely, which would just add to the clamour of

theories all over the internet, I have made it

a mission to try to compare and explain the most important publications

of modern authorities, so that their contexts can be understood. For example, an

attempt is made to explain the different reference

numbers used by different authors for the same old documents.

Names

were variable in the 12th century, making identification of

individuals

difficult and discussion confusing because different modern authors

have different favourite ways

of referring to people with such flexible names. So for easy

reference, names in bold are the standardized ones used by

Katherine Keats-Rohan for individual entries in her two books Domesday People (DP)

and Domesday Descendants

(DD).

I have also been able to refer to the related COEL database which gives

more insight into the reasoning behind those two books, and helps compare that reasoning to a broader literature.

The

starting point for work has been to study the Hastings family of Little

Easton

in Essex, and from there, to move towards their relationship (by

marriage it seems) to the Hastings

dapifers of Bury. As will be shown, this second family also had

connections to Warwickshire and Leicestershire. They are the subject of

a more detailed discussion in a second webpage. Not considered are the

"Hasteng" family of Hastings Leamington (also in Warwickshire); the "Hastings or Eton" family of Eaton Hastings

in Berkshire; nor any Sussex Hastings families including the

apparent family found in Sussex and Essex in Domesday (see the second "Willelm de Hastings" in DD), and also the family of "Ingelran de Ou" (DP),

probable sheriff of Hastings itself, whom Keats-Rohan says probably had

descendents with the Hastings surname mentioned in the cartulary of

Ramsey, and possessing land in Huntingdonshire, for example in Gidding

and Liddington.

A note for those interested in heraldry. I have placed one of the most simple and famous versions of the Hastings arms here, or a maunch gules (gold background with a red sleeve on it), but it is worth noting what Clark remarked in the 19th century: first, the maunch was apparently not used by the 12th century Hastings barons of Little Easton

(their de Louvain heirs seemed unaware of any arms at all for their Hastings forbears in that barony); and second,

that they look very similar to the de Flamville arms from

Leicestershire, a family which married in the 12th century to the

Hastings family of Warwickshire and Leicestershire. One of the ultimate

aims of the following discussion is to determine what links if any

there were between these two Hastings families.

1. The Barony of Little Easton.

It

is useful to begin with the Hastings family around whom the most

disagreement

and confusion in published authorities has centred in the

twentieth century, partly so that we can get past this

subject and make sure that other questions are not forgotten, such as

those which potentially connect the 12th century to the more easily

traceable 13th century. To make it clear, I do fear that interesting subjects are being

forgotten, but we must deal with those which capture the attention first.

The Domesday Book generation

This barony evolved from part of the holdings registered in the Domesday book of 1086 as being held by Walter the deacon.

It is first referred to in the 12th century (around 1177 according to

Clarence Smith p.2) as simply the Barony of Robert de Hastings, but it

came to be named after one of its parts, the Barony of Little Easton. This Easton was sometimes then called Eystan ad Turrim

because there are many places

named something like "Easton" in England, and this one had a tower.

This is in the hundred of

Dunmow in Essex, and was the part of the barony which became its "caput"

(or "head") by the time that such things become tolerably clear. By the

13th century, the Hastings family had been and gone here, replaced by a

branch of the de Louvain family (apparently from Louvain in Belgium) one of whom had married the last Hastings heiress in 1299.

Keats-Rohan names Walter's entry in

her Domesday People,

"Walter Diaconus".

We can say very

little with any certainty about

Walter, including whether he was Norman or Anglo-Saxon. For

example one argument for him being a Norman, is simply that he held a lot of land

in 1086. (See for example Clark p.121.)

As pointed out to me by Rosie Bevan, another reason he is probably

Norman is his name. Nevertheless, he clearly had strong connections to

some of the local

English families, as can be seen by examining what information we have.

Many Anglo-Saxon families who managed to continue holding lands also

had

Church connections, something which Normans and Anglos-Saxons shared a

respect for, and as will be seen, this deacon's family (like many

Norman and

Anglo-Saxon families) had such links.

Around

1086, this Walter

was a reasonably well-endowed tenant-in-chief in Essex and

Suffolk. He also had under-tenancies in that area, as well as

individual manors held "in chief" (directly from the King) in Dorset (Cerne) and Gloucestershire

(Sezincote,

in Celfledetorn hundred), further away in the

west of south England. Both of these remoter holdings

had been held in 1066 by a man with the

common Anglo-Saxon name of Godwin. Dodwell (p.145) points out that the

barony later included both Sezincote and if not Cerne itself,

Godmanston, 2.5 miles from Cerne and not distinguished in the Domesday

Book. Clarence Smith (p.112) suggests not only that this must have be

the same Godwin in both places, but also that the later name Godmanston

is derived from his name. His reasoning is that the two places

continued to be linked. As late as 19 Edward III, 1345, they were

counted together (Clarence Smith p.1).

Some of Walter's lands belonged, or had belonged, to his brother

named Theodric (or Tedric), who was probably dead before 1086.

This brother may or may not then be the

same as the "antecessor"

of Walter (either ancestor or predecessor) who was called Theodric,

and who was also mentioned in at

least one place in the Domesday accounts, "Weledana" in Stowmarket.

Walter may in other words simply have come to hold the lands of a dead

elder brother. On the other hand Theodric (modern French Thierry,

modern

English Terry, or Derek as Clarence Smith preferred to call him) may

have been the name of younger brother, whose lands Walter held as a

guardian. More complex options are also possible. Walter may indeed

have had two close relatives named Theodric, one younger, one older,

and one being Walter's brother - a father and a brother, or a brother

and a nephew for example. So Clark (p.129)

proposed for Walter not only a more certain brother named Tedric, but also a

less certain father with the same name. And with a different solution

Keats-Rohan suggests that Walter's

more certain brother ("Theodric [ ]" DP)

might be the dead predecessor, who had a less certain son of the same

name who was still alive in 1086. She describes him primarily as the Domesday tenant of Peter de Valognes ("Petrus de Valognes" DP,

a

Norman) in Saxlingham, alive in 1086 (so either the record is an anachromism for the father, or refers to a son). This idea

apparently derives from Dodwell, but Dodwell's ideas were also

developed by Clarence Smith.

That

there was a surviving line from Theoderic seems confirmed by the

evidence recited by Dodwell and Clarence Smith. Clarence Smith

(p.113), while questioning the wording of his predecessor Dodwell on

this matter, nevertheless agrees on a basic point which

Keats-Rohan also apparently accepts:

Although

it is unfortunately not true to say that "in Domesday Book the lands

which Theoderic had held were carefully distinguished from those

of his brother," it is true that nothing specifically ascribed to

Theoderic or Derek passed to Walter's descendants; and it would be

legitimate to guess, even in the absence of all other evidence, that

whatever did not pass to Walter's descendants belonged to Derek, Walter

being merely in charge during the minority of his heir.

Furthermore:

At

the resignation of William de Bacton in favour of his maternal uncle

Roger de Valoignes, the Bishop enfeoffed the latter to hold these fees

"as well as ever did Teodericus or his son Hugh." It is therefore quite

clear that Derek had been succeeded by his son Hugh; and since William

de Bacton had a brother Hugh de Bacton, a monk, it is possible that

William was also a son of Derek, having succeeded on his brother's

accepting the tonsure.

Keats-Rohan refers to William of Bacton as "William de Bachetun" (DD), and he was a grandson of "Petrus de Valonges" (DP), through his mother "Muriel de Valognes" (DD)

and her first husband, whose name is never mentioned in contemporary

documents. This first husband was therefore probably either

Theoderic himself, or a son. Apart from

Hugh son of Theodric, and William of Bacton, she also lists another

apparent descendant as "Willelm

filius Theoderici" (DD)

who witnessed the foundation charter of Binham. (Rosie Bevan suggests

to me that William de Bacton and William son of Theodoric are probably

the same person. See her Medieval Genealogy post from 2004.) These holdings of

Theoderic, eventually equating to 13 knights fees in Norfolk and

Suffolk, became

the Honour of Bacton.

The Domesday book records that some of

Walter's and Theodric's lands

had been held at the conquest in 1066 by

a man with the common Anglo-Saxon name of Leuuin (which is the normal

Norman representation of Anglo-Saxon Leofwin), who was

specifically described as a

King's thegn or freeman "of Bacton". Dodwell thinks all Walter's

holdings which came from Leuuin were Theoderic's, and although not all

are specifically named this way in Domesday, Clarence Smith thinks this

a reasonable supposition, partly with an eye upon the fact that they

also all descended together not to the Barony of Little Easton,

but into the Honour of Bacton, which as explained above became a

possession of the de Valognes. As shown above, this was held

by William de Bacton under the Bishop of Norwich, though at Domesday

they had been held direct from the King. (As Rosie Bevan points out to

me, William is known to have owed 80 marks to the Bishop which had 8

fees as pledge. The subsequent transfer to Roger de Valognes of 13 fees

would be because Roger paid the Bishop.) Despite the Domesday book

implying otherwise, the Bishop claimed to be overlord back to the time

of Theoderic and Hugh, so there is some

chance that William of Bacton had not inherited from Theoderic and

his son Hugh, but it seems very unlikely (Dodwell p.157, Clarence Smith

p.114). Clarence Smith

(p.114) even speculates it as a possibility that Leuuin was the father

of both Walter the deacon and Theoderic (Derek, Tedric) his brother. If

so then Theoderic received his father's lands, and they were more

valuable. Dodwell (p.147) lists what she considers the lands of Lewin,

which came to the honour, as

Bacton, Milden, Witnesham, and Brunton in Suffolk, and Purleigh, Colne

and probably Bowers Giffard in Essex.

What

apparently stayed in Walter's family, his own core lands as opposed to

Theodric's, were 7 manors equating to 10 knights fees, which is the

future barony of Little Easton (Clarence Smith p.119). The way the

manors were counted

were four in Essex (Little Easton, Wix, Little Bromley and Little

Chesterford), two in Suffolk (Bildeston and Swilland), and one in

Dorset (Godmanston). Sezincote in Gloucestershire was not separately

counted (Clarence Smith p.1), and there were probably other properties

which also did not count as manors. Five of these seven manors had been

held by the

Anglo-Saxon

Queen Edith, widow of King Edward the Confessor. She had been one

of the greatest landholders in England

but in Wix, in

Tendring hundred,

it is specified that the old Queen

granted this to Walter after the conquest. Later charters of his

children mention that he possessed the house and gardens surrounding

the church at Wix. Based upon the use of the names Edith and Alexander

for children, still very unusual at the time, Clarence Smith wonders

(p.112) if Walter the deacon married an Anglo-Saxon lady, as the

name Alexander was then probably associated with St Margaret, queen of Scotland, as she also had children with these

names a little earlier, and her court was well connected to the old

defeated Anglo-Saxon nobility. According to Clarence Smith, St Margaret was a

source of inspiration for people looking for names for their children.

And because Walter's son Alexander, though not his eldest son,

inherited from his daughter Edith, as we will see below, Clarence Smith

suggests that these two and also their brother Walter Maskerel shared

this Scotland-watching mother, who must have been a second wife. Query.

The logic of Clarence Smith actually seems to imply that Walter

Maskerel, as the elder brother in this group, can not have had the same

mother, for he did have an heir as will be seen below.

Apart

from Godwin, Leuuin, Theodric, and Queen Edith, there was one more

known predecessor of Walter's Domesday holdings (at least just sticking

to the manors held in chief). Little Easton itself had been held by

someone named Dodinc, who Clarence Smith says appears nowhere else in

Domesday.

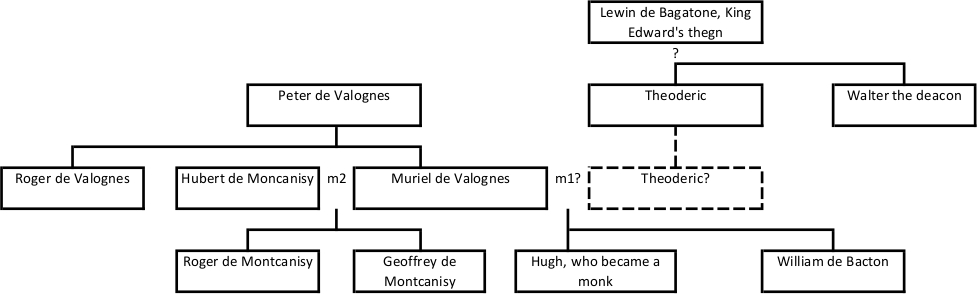

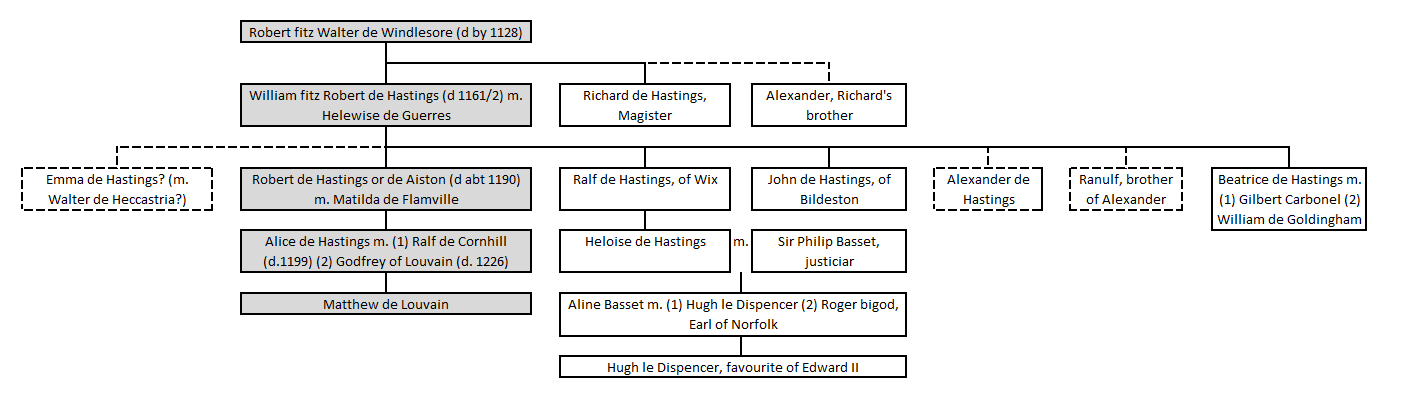

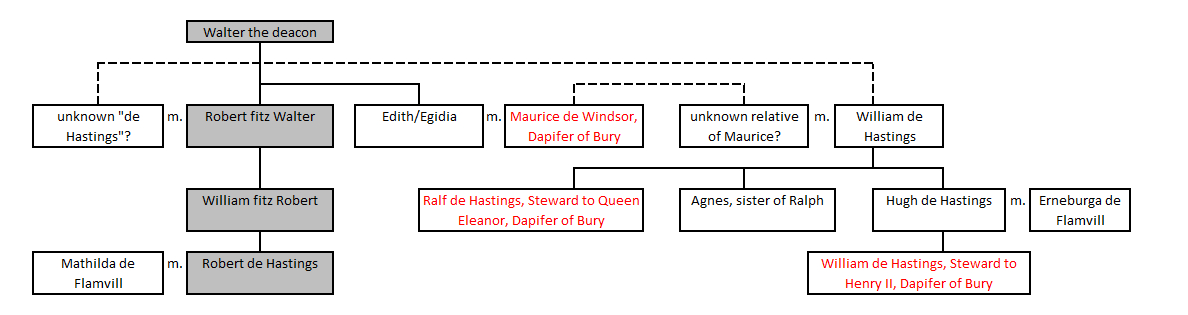

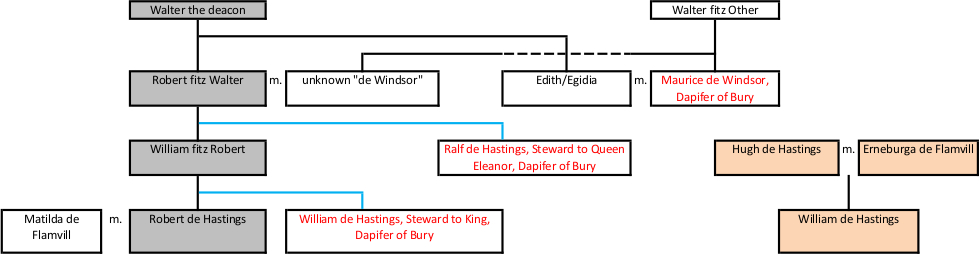

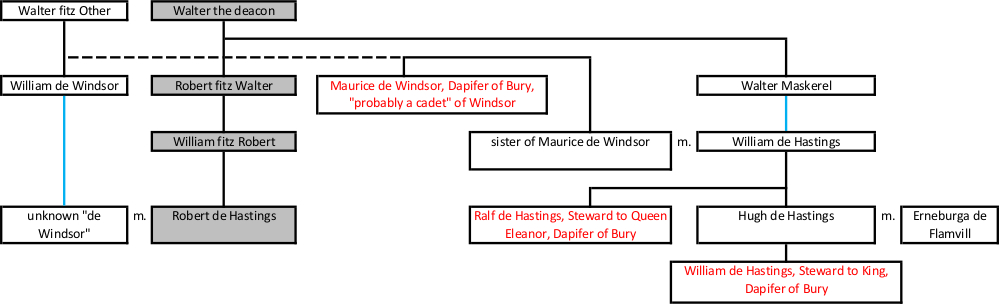

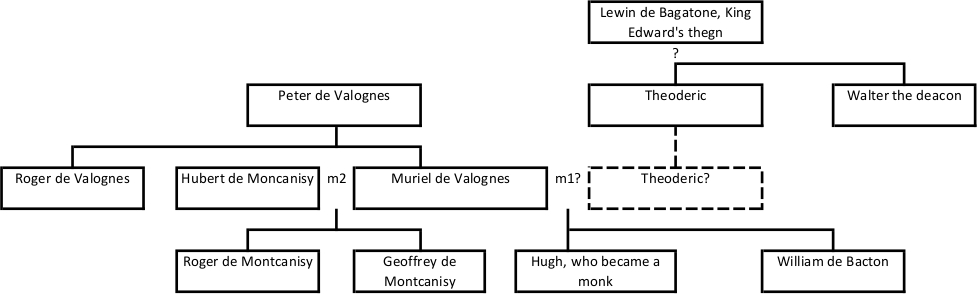

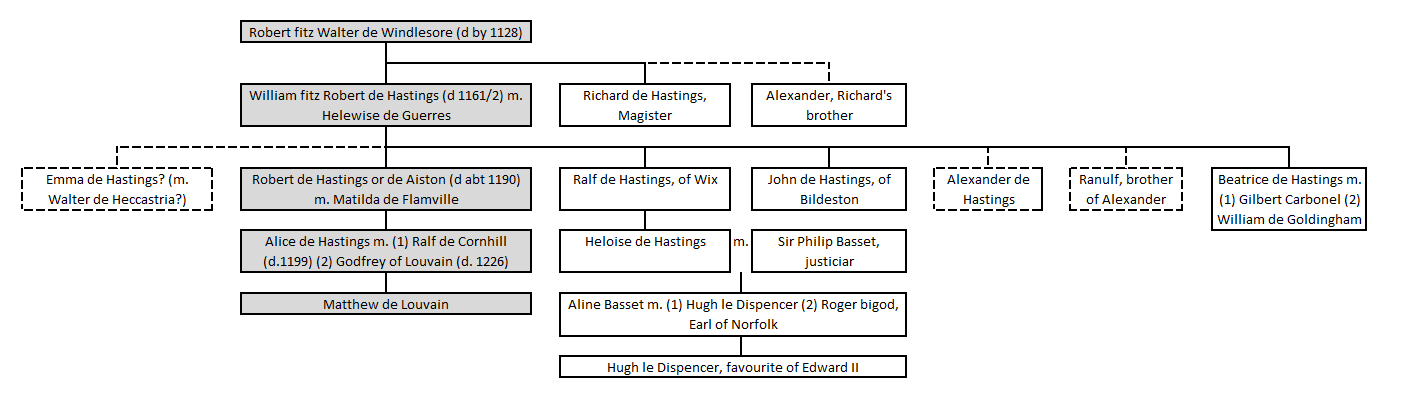

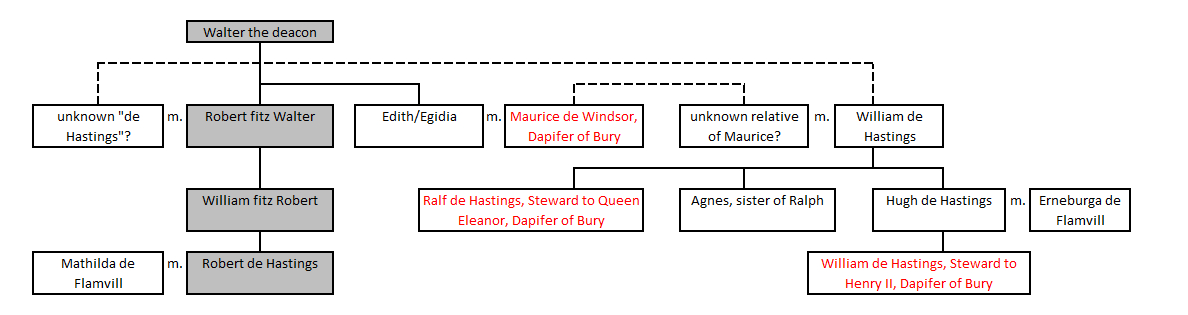

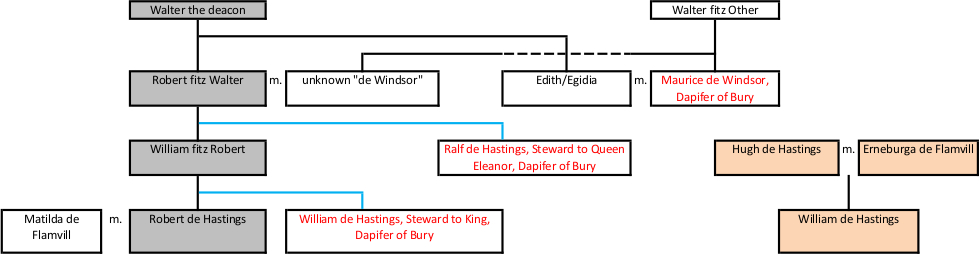

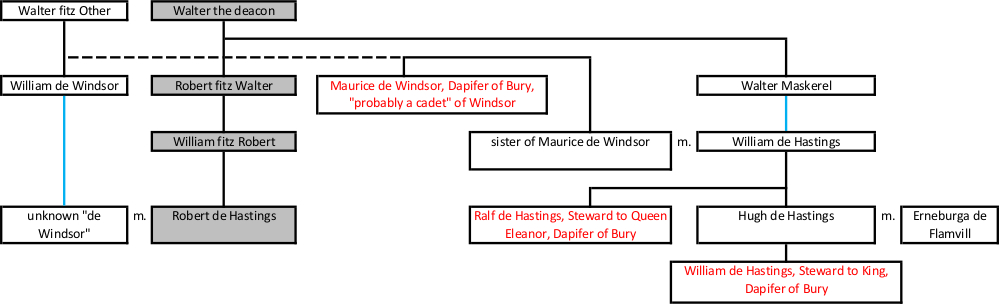

pedigree 1. A tentative pedigree for the 11th century generations

A controversy

A

famous debate

exists concerning the next generation after Walter, which possibly

attracts more attention today than it deserves. It arises because the

next

man known to be

holding this barony, Robert, is thought by some

to have sometimes been described in his own lifetime not with any

Hastings surname, like his descendants, but as Robert "of Windsor"

(with the

many spelling variants of the time such as de

Windelshore, or Windresore and so on). Keats-Rohan for example, in her

entry for

him in Domesday

Descendants, uses the name "Robert de Windresor",

although she mentions that in family charters relating to his

succession he is called Robert fitz Walter (Robert son of Walter). As

will be discussed further below, it seems reasonable to doubt that he

was ever called Robert of Windsor in

any document,

but in a much-cited

charter

of 1128, which exists in two later transcribed forms, King Henry I

refers to him in Latin as "Robertus filius

Walteri de

Wyndesora" This could simply be read as a description "Robert son

of

Walter, of

Windsor", or "Robert, son of Walter of Windsor". In this period there

always have to be doubts that words like the "son of Walter" or the

"of Windsor" were being used as a heritable surname, or just

descriptions, but this is a

possibility. The charter said that he had

died and that William, son of this

Robert, had been rendered his father's lands by the king.

(When looking at collections of royal charters from this period and

region, such as that of Farrer's itinerary of Henry I, it seems likely

that such a specific name was needed because of possible confusion with

other men who might have been Robert, and whose father might have been

Walter. One such, though a bit too young to be confused with this one,

was for example the founder of a famous de Chesney family, "Willelm filius Robert de Caisneto" (DD).)

This charter is found copied in the Calendar of Charter Rolls,

Vol.II, p.137.

The date of the inspeximus was 2 March 1270, Westminster, and two

versions are given, one by Henry I shows Maurice de Windesore as a

witness. Landon (p.175, n.3) informs that the original date was 1128

based upon William Farrer's Itinerary

of Henry I, p.124,

wherein charter 579 is an English translation of this announcement. The

second old charter in the inspeximus is according to Clarence Smith

(p.106) by Henry II.

Farrer also informs that there was another inspeximus of this record 10

April 1336, as shown p.249

of the Calendar of

Patent Rolls,

for Edward III, Vol.3. Clarence Smith (p.107) explains that the

original charter also survives, Harleian manuscript 43, c.22, published

in facsimile in Warner and Ellis (1903) as plate 39; Bishop No. 376).

A widespread confusion arises because a Walter "of Windsor" did

exist (although he was probably never named this way). John Horace

Round, especially in

the second

part of his 1902 article

on the "Origin of the Fitzgeralds," insisted that Robert must be a son

of this Walter fitz Other ("Walter filius Other" DP),

who held the castle of

Windsor for

the Norman king, and whose sons and descendents were often

understandably referred to as being "of

Windsor". (But Clarence Smith, p.107, points out that "even Round does

not claim that Walter fitz Other ever called himself de Windsor".) But

this raises a question of why Walter the Deacon would

make the son of another man his heir when he had, as we shall see, sons

of his

own. Indeed, Walter fitz Other himself had another heir, "William filius Walteri filii

Otheri" (DD). (See for example the first

part

of Round's Fitzgerald article. The barony of this family

is referred to as the barony of Eton, in Sanders (pp.116-7) for

example.) The only way to explain it according to Clarence Smith

(p.105) would be forfeiture whereby, as a "gesture of reconciliation",

the king effectively demoted Walter and his male line, putting in a new

man above him, who as an "act of reconcilation" married a daughter of

Walter. (In this case Clarence Smith finds it difficult to accept that

this Robert de Windsor, not known from other records, would be so

highly favoured with his marriage. For example a highly favoured man,

Maurice de Windsor, married a younger sister.)

Round's thinking on this matter was apparently strongly connected to a

well-known article,

which he published that same year, on "Castle Guard".

Round showed

how

the barony of Little Easton owed castle guard to Windsor. So

although the Little Easton Hastings family held directly of the king,

in another way they were answerable to

the

Windsor castellan family, giving the barony of Little Easton an association with that

castle. The Red

Book of the

Exchequer, Vol.

II pp.716-7, is

one of the only clear records remaining of the make-up of a castle

guard

barony from this period. It shows that Matthew de Louvain, the heir to

the Hastings

barons of Little Easton in the 13th century, was one of the major

castle ward tenants of

Windsor, holding 10 knights fees. 10 knights fees is the same as the

barony reported in the Cartae

Baronem

in the mid 12th century for his Hastings forbears. If I

understand correctly, in the time of Robert castle

duty would still have involved real duties and a physical presence at

the castle in the early

period. That would

seem to give a possible explanation for the use of this second name in

this specific Essex barony (Clarence Smith p.107), because the men of

the Little Easton family had to work and fight for the men of the

Windsor family. But designations

such "de Windresore" can not be assumed to be inheritable family names

in the early 12th

century, and certainly not in the family we are discussing.

Nevertheless, Round was scathing and dismissive of the 1869 attempt of

G. T. C. Clark

to argue

(as had Eyton before him) that Robert was the son of the Deacon, and

authors in following

generations such as Landon, Moriarty, Sanders, and Dodwell seem very

reluctant

to

disagree with the great Round, even though especially Landon and

Moriarty pointed

readers

to doubts about the arguments presented by Round.

In the 21st century one of our most well-known contemporary authorities

for

these generations, Katherine

Keats-Rohan, has taken a strong position in favour of the Deacon as

father of Robert, in disagreement with Round. Unfortunately, for a

large part of the genealogically-inclined public, the reasons for

accepting such a position seem not to be well understood. In fact,

the most complete statement for

this position, which took into account all the previous authors, had

been published by Clarence Smith, but this is not available on the

internet, and apparently not widely known. Some of the details of

Keats-Rohan's position can be gleaned by comparing entries in her Domesday Descendants,

especially for the second names "de

Windesore", "de

Wikes", "Mascerel"

and "de Hastings",

but she also gave some specific (but short) explanations in both the forward of Domesday Descendants

(which

includes a Hastings pedigree), and a Prosopon

newsletter

about early baronies where she disagrees with the standard work of

Sanders. It behooves us nevertheless to

explain how strong the

case is that Round is wrong and Keats-Rohan is right, because:

- The well-known printed reference

works of

Keats-Rohan are in a specific format, containing short statements about individuals who can be

identified from a certain set of documents in a certain period.

- The two books

also do not present exhaustive

sourcing or arguments, which are however somewhat more traceable in the COEL

CD-ROM.

- Keats-Rohan's own printed statements on this issue have for better or worse tended to focus

on one

particular aspect of evidence which is open to debate. The

following quotation is presented as the core argument:

The relationship is

established by the fact that Henry II’s charter

giving the stewardship of Bury to William his dispencer is very

specific in its description of the relationships between William and

his predecessors in the office. William’s immediate predecessor was his

paternal uncle (patruus) Ralph I of Hastings, a son of Robert fitz

Walter; Ralph of Hastings had inherited the office from his maternal

uncle (avunculus) Maurice of Windsor (his mother’s brother who had

probably derived his right through his wife Edith).

The charter being referred to is for example reproduced as Bury charter 89 (Douglas ed.).

Henricus

rex Anglorum et dux Normannorum et Aquietanorum et comes Andegauorum

archiepiscopis. episcopis. comitibus. baronibus. iustic'.

uicecomitibus. et ministris et omnibus hominibus suis francis et anglis

salutem. Sciatis me concessisse et carta mea confirmasse Willelmo de Hastyngs dispensatori

meo

dapiferatum sancti Edmundi. Quare uolo quod idem Willelmus et heredes

eius habeant et teneant dapiferatum illum bene et integre et in pace

cum omnibus pertinenciis eius in liberacionibus et feodis et

innominatim cum Legata et Bluneham et aliis locis et rebus eidem

dapiferatui pertinentibus sicut Radulfus

patruus eius

eum melius habuit et tenuit uel Mauricius

auunculus suus eiusdem Radulfi.

Testibus. Willelmo Malet dapifero. lose [sic] de Baillol. Alano de

Nouilla. Willelmo de Lanuolei. Hugone de Loncamp'. Hugone de

Gondeuilla. Hugone de Piris. Waltero de Donstanuilla. Roberto filio

Bernardi. Per manum Stephani capellani et cantoris mei. Apud Porcestram.

It seems that letting the published explanations rely on

this later royal charter has left doubts amongst well-informed

readers

concerning the link between Walter the Deacon and Robert. Is this

evidence strong enough to disagree with someone as famous as Round? The

doubts

seem easy to explain:

1. This is a philological explanation which relies on the use in this charter of two distinct

words for

uncle, one paternal and one maternal. However, the word avunculus

was not always used to strictly refer to maternal uncles, but could

also mean

"uncle" more generally, like the modern English word. A very relevant

example is that Robert's own son William

referred to Walter Mascerel and Alexander of Wix as avunculi

(Landon p. 175, citing charter A.5275;

also Clark p.124). Whereas

Round would say they were maternal uncles, in this case Keats-Rohan

would say that they were actually paternal uncles. Undoubtedly

we must consider that in the document Keats-Rohan relies

upon, the

two words, patruus

and avunculus,

are together in one document made for Henry II. So the words

appear to be used in a precise and considered way. A

weak counter argument still exists however, because it

appears

possible that the word choices of this charter might have partly been

decided by looking at older charters about the descent of this

stewardship.

We can compare charter 87

in Douglas' edition of Bury charters, granting to Ralph of

Hastings that which had been held by "Mauricii de Windelsore auunculi

sui". The later royal charter, focussed upon by Keats-Rohan (charter

89),

could be read as repeating the old one when it says that Maurice had

been avunculus

to Ralph de

Hastings. In any case, can we be sure that the composer of this wording felt certain

they were using exact terminology, as opposed to simply an old

authority?

Nevertheless,

it seems reasonable to be believe the word selection in this charter

was intended to mean something, at least

concerning the relationships between the people mentioned in it. And

indeed the

relevance of this charter's two types of uncles was apparently

first noted

by Eyton, and in this he was followed by Clark and Moriarty, and this

is the

basis of pedigree 6 below. But is it relevant to the question of Robert

and Walter? And is it strong enough to be certain that Round was wrong?

2. The second and more important problem with this way

of presenting the argument for Robert fitz Walter being the son of the

deacon is that this charter only gives indirect evidence on that point.

The charters about the

dapifership of Bury do not mention

Robert, or his father Walter, or anything directly related to the

Barony of Little Easton, and so everything seems to hang upon the

assertion of Keats-Rohan that the

person she calls "Ralph

II of Hastings"

(DD),

who we shall discuss below, was a son of Robert fitz Walter (DD "Robert de

Windresor").

In short, in

order

to use this charter to define the relationship between Robert and

Walter, we need to know how these dapifers of

Bury themselves related to Robert and Walter, but there is

at least some room for doubt concerning the relationship between the

Hastings families of the lords of Little Easton (pedigrees 2-5 below),

and the stewards of Bury (see pedigrees 6-8 below). Indeed, as I will

explain, Keats-Rohan's understanding of this relationship is unique,

and hard to justify.

Other evidence is however available, which can allow us to first

try to establish the descent of the Barony of Little Easton, before

returning to the subject of the above-mentioned dapifers, William, Ralf

and Maurice. The evidence was presented in

the 19th century Hastings articles of Clark, which were so

vigorously (but not rigorously)

attacked

by Round. Pedigrees 2 and 3, define what is relatively uncontroversial

about

the relations of Walter and Robert respectively, using charter evidence

which Clark started to gather in the 19th century, but which (less

well-known amongst genealogists) has been substantially improved upon

in the late 20th century by Landon, Dodwell and Clarence Smith. After

defining these as starting points, we can try to close the case

concerning the father of Robert fitz Walter, by adding pedigree

4 which allows to link the first two, giving us pedigree 5. The

evidence from legal records presented in pedigree 4 was already given

by Clark. Remaining

doubts, including those explained by Barbara Dodwell in 1960 (see

Bibliography), will be noted where relevant. However, Clarence Smith's

more recent articles (1966 and 1967) contained replies to those

concerns which supports the following summary.

Keats-Rohan

cites Dodwell, who she apparently disagrees with on this point, but

possibly she was not be aware of Clark's and especially Clarence

Smith's articles, which do agree with her.

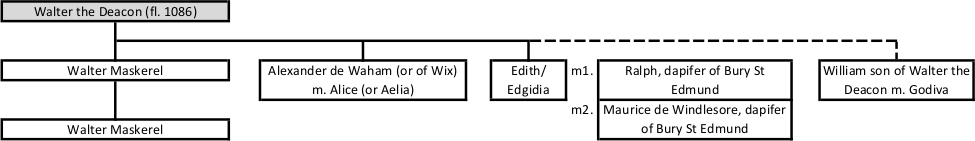

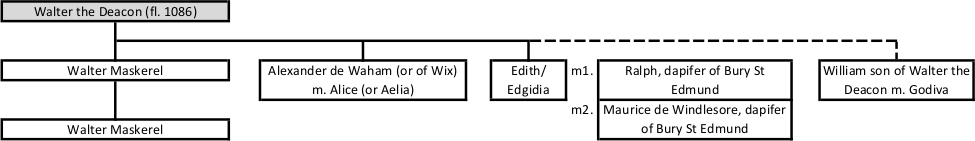

pedigree 2. Walter the Deacon and the children named

as such in charters (none of whom took over his lordship)

Note:

The lords of the barony in each generation will be distinguished by being

in shaded boxes.

Notes for this pedigree.

1. The fact that Walter the Deacon had three known children has

been treated as certain by authors since the time of Philip Morant, but

in the 20th century, Dodwell found reason to doubt he was their father.

Various charters

summarised by Clark, Landon, Dodwell, Clarence Smith and others

uncontroversially confirm that Walter Maskerel,

Alexander de Waham (or "Valham", or of Wix) and a sister named Edith

were siblings and benefactors to the nuns at Wix. Especially useful are

a series of them concerning a house and lands surrounding the church at

Wix, which had belonged to their father, but the oldest of these

documents do not name the father. Discussion is required to consider

the evidence for the father's name:

- From the time of Henry I, when Walter Maskerel was still alive,

there is AS.316 (E42/316). This was selected for National Manuscripts in Facsimile I, No.5, Bishop No.493, and is discussed by Clark (p.125 though he had no standard reference number for it), and Clarence Smith (p.11). It is also Charter 1739, p.258, in Regesta Regum Anglo Normannorum

Vol. II. The

charter also grants two carucates and seven villeins at Wix, and 10

shillings worth of land at Fratinges. It lastly mentions the isle of

Sirichesie and the tithes of Purleigh, but Clarence Smith (p.11) points

out that this does not appear in later confirmations, and while these

were certainly granted (as shall be explained) they were not held under

the same tenant in chief and their grant had a different history.

Therefore he considers the inclusion on the end of this grant

"suspicious". Brook (p.46) lists it as document i, in his extensive

list I, of probable forgeries among Wix charters (copies made later

than they purport to have been made). Brook also mentions that the

charter was reproduced because of a later inspeximus in the Patent Rolls of Henry VI, p.262, p.263.

- King

Stephen's confirmation "again uses almost identical language" except

without mention of Sirichesie and Purleigh (Clarence Smith p.11) and so

once again does not mention the father's name. It is E40/5276,

also known as A.5276, in the "A series" of "Ancient Deeds" at the National Archives in Kew. In older Cartae Antiquae terms this is L.2.31.4, and according to Clarence Smith was cited by Clark p.123 wrongly as L.2.31.14. Clarence Smith also refers to it as Bishop No 449. It is also found in Regesta Regum Anglo Normannorum

Vol. III, charter

960,

p.355, and Keats-Rohan

cites this one. Brooke (p.45) felt it probably a genuine original

(p.46, n.2): "If it is a late twelfth-century forgery, it is

a very clever imitation of the real thing, and it shows no

resemblance to the hand of either known forger".

- Alexander

made a charter after the death of Walter his elder brother, and

addressed his confirmation of this grant to Bishop Richard of London.

This is Bacton Charter number 10 in Dodwell's article, dated by

Dodwell 1157-1162. This is also E40/5273, formerly Cart. Ant.

L.2.31.14, and also noted by Landon p.174. Brook (p.47) includes it as

charter viii in his list I of probable Wix forgeries. (Brook associates

it with charter E42/301, which is one of the grants concerning another part of Wix manor.) NOTE: This particular charter after the death of Walter is also made at the plea of his sister Edith.

- William

fitz Robert, the lord of the barony of Little Easton at that time, also

apparently confirmed the above grant of Alexander, or at least "all

that donation which my avunculi Walter Mascherel and Alexander his brother gave". This is E40/5275, formerly Cart. Ant. L.2.31.10, cited as such by Clark p.124.

(Clarence Smith is wrong to suggest Clark cited it also on p.121.)

Brook (p.47) lists this charter as number x in his list I of probable

late copies.

- Henry II's confirmations do name the father. There are two versions. E40/13947 was copied very early into the Cartae Antiquae Rolls. Brooks (p.53) suggests this was done by 1198, not long after he thinks it was itself made. Landon describes it as Carte Antique No. 3; Clark p.123, p.125 as Cart.

Ant. Rot.

c.m.20 dorso; In Dugdale's Monasticon

IV p.513 it is reproduced and referred to as Cart. Antiq.

c.n.20 (which Clarence Smith refers to as a "very faulty" transcript).

Brooke lists it (p.46) as charter iii in his list I of probable

later copies from Wix, and done in forgery "hand I". A plate of it

was reproduced, and discussed p.16, in Jenkinson's book on Paleography.

- The second Henry II charter is E40/14901, also reproduced in Jenkinson, and has other references National Manuscripts in Fascimile I, No.11, Bishop No.481.

Brooke lists it as charter xxiii in his list II of probable forged

copies, and it was done in "hand II". He suggests (p.46, n.1) that

E40/14901 was possibly copied from E40/13947, "but they may well be

approximately contemporary". Brooke indeed mentions (p.54) these two

documents as evidence that the two professional forgers must have been

working for Wix at a similar time in the 1190s. (It must have been a

major project.)

In general, both Brooks and Dodwell acceept

that the "forgeries" were probably simply copies commissioned by the

nuns because of extensive damage to their important deeds. What was

forged were the seals and other evidence of the documents being

original. But specifically in the case of Walter the deacon they

propose that something might have been added, and in particular one of

those things is the name of Walter the deacon, who is, they note, actually referred to here as Walter the dean (decanus), not the deacon (diaconus)

as in the Domesday book. Brooks (p.53) even argues that the name

might simply "have been invented in the 1190s" and the basis of this

position is that it "gives a very inflated list of privileges and

exemptions". In other words, in this one case he thinks the nuns really

inserted new information fraudulently, and Dodwell (p.150) apparently

accepted this. Clarence Smith finds this logic defective, saying

that such an insertion could have served no purpose in the 1190s, and

that "it is surely an exagerration to say that 'it gives a very

inflated list of privileges and exemptions' " (p.104). Concerning the

insertion of Walter's name, he proposes that an example of a simple

explanation would be that Alexander, "alive in 1157 but an old

man", took advantage of the fact that Henry II was writing a new

confirmation, of which the original is now lost (and which "does not

purport to follow the exact words of its predecessors"), in order to

"rescue his father from the oblivion of anonymity".

2. The

husbands of Edith are important to the overall story, and also require

detailed explanation. Two proposals made in the 20th century have now

received apparent acceptance, but the evidence is not apparently

well-known. The apparent identity of "Edith soror Alexandri de Wikes"

(DD) (the one who plead to Alexander that he mentions in Bacton Charter 10) and the Edith (or Egidia) who married "Maurice de Windresor"

(DD) seems to have been first noted by

Landon, and for example G. A. Moriarty adapted his conclusions after

reading Landon, publishing a second Hastings article in the New England

Historical Genealogical Register. Dodwell, Clarence Smith and Keats-Rohan also accept

this suggestion. Apart from the

coincidence of name (which apparently appears in very varied forms in

the original documents), the coincidence of an interest in Wix is not

conclusive because other people "of Windsor" were also benefactors in

the 12th century (see Clark, and also Dugdale's Monasticon

IV p.513),

and also being called "of Windsor" was not necessarily a family name.

The evidence really has to be sought in charters again. That Edith had

first married Maurice's predecessor as dapifer of Bury, known simply as

Ralph the

dapifer2.,

was apparently first proposed by Dodwell, and is accepted by Clarence

Smith and Keats-Rohan. That one of them was probably related to Ralph

had been noted at least since Eyton.

- A charter E40/8923 by Maurice and Edith together to

the nuns, grants the

isle of "Sirichesie" and

the tithes of "our demesne" Purleigh. Clarence Smith discussed this

charter p.109, and it is reproduced as Dodwell's Bacton charter 7

(p.162), dated 1154 or 1155. Importantly, this charter made it

clear that

this

was from Edith's inheritance. (Sirichesie is possibly

Northey. This was proposed in a short note by

R.C. Fowler based on Landon's paper, and published in the same

journal. Brooke, Dodwell, and Clarence Smith apparently accepted

this identification, all citing Reaney's Place Names of Essex p.218 as an authority.)

- Dodwell

mentions (p.154) that E40/14542 is a papal confirmation of this

grant, which specifies that Maurice and Edith did not hold "Sirrshseie"

and "Purlai" of Little Easton, but of Holy Trinity in Norwich. Dodwell

concludes that these holdings were not part of Walter the deacon's own

core possessions, but actually part of Theodric's original holdings

which somehow came into the hands of the sea of Norwich. But as

discussed above, most of these continued to be held under Norwich in

the Honour of Bacton.

- Dodwell's

Bacton charter 2 (p.158) is a

charter of William of Bacton, dated 1121-1135 concerning all his lands

he held under Bishop Ebrard, worth 13 knight's fees, to be granted to

his maternal uncle Roger de Valognes. But for some reason it was

necessary to mention that the grant specifically excluded lands held

directly under the bishop by "Maurice" which Dodwell (p.154) and

Clarence Smith (p.114) believed to be Maurice de Windsor.

The implication, also suggested by the odd number of 13 knight's fees

in this period when most were multiples of 5 still, is that the lands

of Maurice had once been held together with the rest of these lands,

presumably by Theoderic. The suggestion is that these were two manors

at Purleigh, the same as Maurice would grant with his wife.

- In an 1130 charter,

Dodwell's Bacton charter 6, Maurice and Edith grant the church of Hoxne

to the Bishop. They wanted a convent of monks to be placed in a

chapel in Hoxne so they might pray for

Ralph the dapifer's soul. They said that Ralph had rebuilt Hoxne St Edmund. This is a

typical thing which would be done for a close relative. Eyton and Clark

in the 19th century

therefore claimed that Maurice must have been related to Ralph.

Dodwell and Clarence Smith say that Maurice and Edith nevertheless were holding on to

possession of lands they held under the bishop in Purleigh, because

Bishop Herbert's confirmation (reproduced within charter 6) mentions

that he and his successors would, if they had occasion to summon

Maurice or his successors, do it at "Purlai" not Hoxne.

- Dodwell's Bacton charter 5, dated by her to between 1110 and 1119, is

clearly the predecessor of the later dedication in charter 6 to Maurice and Edith in

Hoxne, and shows that the lands were originally granted to Ralph the dapifer

and his wife

Edith by Archbishop Herbert de Losinga of

Norwich (d. 1119). The

bishop granted them the church of Hoxne, together with another un-named

fief, until both of them were dead. Dodwell and Clarence Smith concur

that this un-named fief must therefore be Purleigh. An article on Hoxne chapel which is helpful for the subject here is this one.

So it seems Edith did not have Purleigh because it belonged

to Walter

the deacon (as part of his brother Theodric's lands), but rather

because it was granted to her and her first husband. To show that

Alexander of Waham was also the brother of this Edith we need to look

at charters about these lands after Maurice and Edith's time.

- E40/5270 is Cart. Ant. L.2,31

19, and referred to by Clark p.123 and

p.125.

Clarence Smith describes it (p.108) as being made by the Bishop of

London between 1154 and 1160, but reciting that the late King Henry I

had taken the nuns under his protection, including their lands, under

which Siricheseie is mentioned. It is also mentioned that Archbishop

Theobald had confirmed this too. The grantor of the lands is not

mentioned, but it is mentioned that the tithes of Purleigh were by then

in the demesne of Alexander de Walham. Apparently E40/5271 and E40/14542 are similar (Clarence Smith p.108, n.169).

- The

above-mentioned confirmation of Archbishop Theobald also exists, as

AS.356(i) (presumably somewhere in E42 today) and this document says

that the grant was by Maurice de Windsor and

Alexander de Waham. This links Alexander to Maurice and Edith, Edith

apparently having died first, and makes it clear that his

reconfirmations were of the same lands they granted. Alexander seems to

act like an heir to Edith. Similar documents apparently include

E40/14550, E40/14042, E40/5269, and E40/14542 (Clarence Smith p.109,

n.173).

- E40/13946

is what Clarence Smith calls Alexander's

"consolidating charter" (p.12, p.109). It confirmed many old grants,

including the ones about the gardens and house at the church of Wix

discussed above. Clarence Smith thinks it was made in anticipation of

death, including an "unprecedented" number of witnesses, and

arrangements for his wife after his death. Concerning the tithe of

Purleigh, and the isle of Sciricheseia it does not mention any

predecessors, but it does say that it belongs to him by inheritance.

This means he must been an heir of Edith the wife of Maurice.

Apparently the consolidating charter did not explain completely

who would be Alexander's heir in each place, and Clarence Smith suggests that

the one or more of the charters by landlords has not survived which

might have explained this.

- E40/5268 is Cart. Ant. L.2,31 16 and referred to by Clark p.123 and p.126.

It is also Bishop No.448. It is a confirmation by Henry II of

Alexander's grant, along with some other grants by other people. It

does not refer to Maurice or Purleigh. Clarence Smith remarks (p.111)

that this royal confirmation shows that Alexander's claim to hold this

of his own inheritance was taken seriously.

As

it seems Edith and Maurice had no children themselves, and as it also

seems that Alexander de Waham had a sister Edith, the solution proposed

by Landon, and accepted since then, is that Alexander is the brother

and heir of Edith the wife of Maurice. As Clarence Smith remarks, this

implies that Alexander and Edith, who had at least one older brother,

must have shared a different mother.

- We

must also consider the confusing fact that while it seems Edith had

Alexander as an apparent heir, Maurice seems to have also had a man named Ralph de

Hastings as an heir, or at least as someone who was a successor

assigned to some lands he once held. This was long known for the

dapifership, but

Dodwell showed that there is also a charter, her Bacton charter 8

(which is reconstructed from the damaged original E40/6227, plus a

later inspeximus copy annexed to E40/751,

also damaged) concerning Sydritheseye and Purleie and its tithes, held

of the Holy Trinity in Norwich. That this inspeximus was requested by

Henry son of Henry de Hastings shows that this was remembered by the

Hastings family which would become the Earls of Pembroke. Dodwell

remarks (p.155) that it is confusing that Alexander and Maurice,

Alexander on his own, and finally Maurice's own heir as dapifer Ralph

de Hastings, seem to all have acted as heirs at different points. She

thinks Ralph was last in this sequence.

- That Northey and Purleigh came to the

family of the dapifers of Bury is confirmed for example by Dodwell (p.156), who

says that a knight's fee at Purleigh was one of the fees belonging to

Lidgate in the Inquisition Post Mortem of hereditary steward Henry son

of Henry de Hastings (who was probably the same one who confirmed the charter of Ralph, E40/751).

Note:

So far I have summarised the descent of two sets of property, (1) being

the gardens and house around the church in Wix, and (2) being related

to Purleigh, specifically concerning its tithes and the Isle

(apparently) of Northey, which apparently ended up in the hands of

another Hastings family. The family charters and their various

confirmations also mention (3) 20 acres in Wix which had once been held

by a priest named Algar (A.5273, A.13897). This was apparently first a

grant of Alexander de Wikes, which later passed to Ralph de Hastings of

Wix (who is not the same Ralph as the older man who was heir to

Maurice as dapifer, as shall be shown). Another donation (4), which we

can track is 10 shillings worth of land in

Fratinges (AS.316, A.13897). These were originally possibly granted by

Walter, Alexander and Edith together, but later they also came to Ralph

de Hastings of Wix, who called his predecessor Alexander de Wicha

(Clarence Smith pages 10-11). (5) Is a third of the manor of Wix,

which Clarence Smith interprets as a third of a half fee, or a 6th of a

knight's fee. Clarence Smith (p.10, p.101) understands the manor as a

whole to have been held in two moieties by Walter de Maskerel and

Alexander de Waham, but that after the death of the second Walter, Wix

became a manor of half a fee. Alexander granted a third of his part to

his wife as her dowry. Later it seems the two parts, now valued at half

a fee, descended to Ralf de Hastings of Wix, and from him to his heirs.

(6) Are the lands Alexander acquired himself, outside the barony

(Clarence Smith pages 12-13). These also passed to Ralph, and can be

traced to his heirs.

3. Further notes for the above pedigree.

- Walter

Maskerel son of Walter Maskerel is mentioned in the

"ancient deed" A.13881 (E40/13881), in

which his uncle Alexander is a supporter when cousins granted him land in Wix which his

father of the same

name

had possessed. (This shows that Walter, presumably older because always

listed first, died before his brother Alexander.) The possible

continuation of the line of Walter Maskerel shall be discussed below.

- "Alexander de

Wikes" (DD)

is refered to as being of Wikes, or Wix, in E40/5273,

but actually seems to be more commonly referred to as Alexander de

Waham, or simply Alexander. Morant,

apparently thought that Waham referred to Witham. Dodwell (p.151)

suggests it could be Waltham or more likely Wallam, in Bradwell on Sea.

She thought that Bradwell on Sea might also be related to "Excestre" (a

surname also associated with this family, see pedigree 3). His seal, mentioned by Dodwell and Clarence Smith, said "Valham".

- Although I find no discussion of the implications,

Keats-Rohan has an entry for "Willelm

filius Walteri Decani" (DD). (Note: not "diaconi".) He was a tenant of "Roger de Montcanisy" (DD) at Ashfield, Suffolk, and his

land was given with consent of his wife Godiva, to Colne priory. Keats-Rohan cites Fisher's Cartularium

Prioratus de Colne,

charters 67, 68 and 70, which are all dated 1155. Ashfield had not been part of the

deacon's

Domesday holdings, but being in Suffolk, it is not far. On the other

hand the norman de Montcanisy family were related by

marriage to

the family of the deacon, according to Keats-Rohan: "Hubert de Montecanisio" (DP)

married as his second wife, "Muriel

de Valognes" (DD),

whose first husband was probably either Theoderic the brother of

Walter, or else a son. The nature of the grants presumably implies William had no heir.

Many charters remark that Walter and Alexander were uncles (avunculi)

to William fitz Robert, lord of Little Easton in the mid 12th century.

But we delay discussion of that link until we can give evidence

about whether they were paternal or maternal uncles.

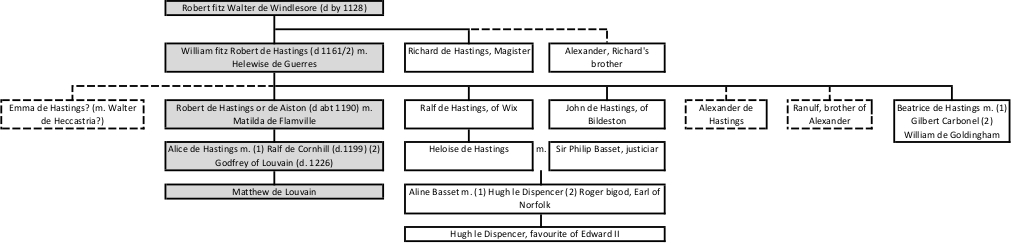

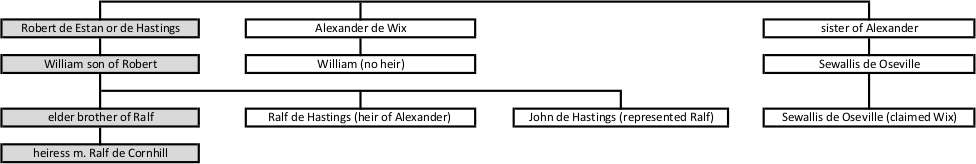

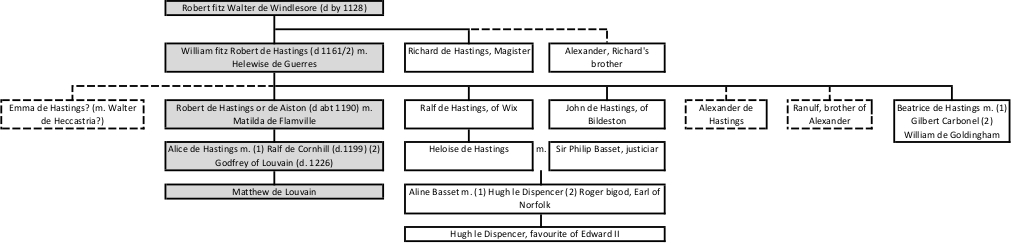

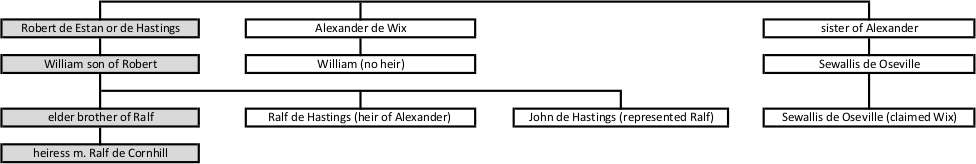

pedigree 3. The lords of the

Barony of Little Easton, after Walter the Deacon

No charter evidence says which Walter was the father of Robert fitz

Walter, and so to begin with we examine the charter evidence for his

family in isolation.

Notes for this pedigree.

1. Robert in the first generation.

There

are very few near-contemporary documents mentioning Robert directly. I

have mentioned above that I have doubts that he was ever referred to by

the name Keats-Rohan uses in her

entry for

him in

Domesday

Descendants,

"Robert de Windresor". But (as already discussed) in a

much-cited

charter

of 1128, which exists in two later transcribed forms, King Henry I refers to him in Latin as "Robertus filius

Walteri de

Wyndesora". Clarence Smith (p.107) says that the only other clear mention of him is in the

Curia Regis

rolls, some generations later, wherein he is once called "de Estanes"

and once "de Hastings". There are several cases of Robert de Windsors

as witnesses in charters

in the 12th century for this family, but most of them are too late for

this Robert, and clearly represent a younger man of that name. See for example Bury charter

138

(estimated 1148-1156). While Keats-Rohan speculates that this

Robert,

who she calls

"Robert de

Windresor II" (

DD),

might represent a branch of the deacon's family who kept using the name Windsor,

he is in any case likely to be another kinsman to Maurice, and/or probably

also related to the Windsor family who were tenants under the barony of

Little

Easton in Swilland, as shown in the

Red Book of the Exchequer

for 1166 (p.358). (Clarence Smith believed the Swilland de Windsors to

have a confirmable connection to the family of the castellans.)

Keats-Rohan only cites two Bury charters

108 and

109

(both estimated 1114-1119), as documents where a Robert de Windsor is a

witness who she thinks might be this one. They are versions of the

granting of

Maurice de

Windsor of the Bury dapifership. They also have a Reinald de Windsor as

witness. Another from a similar time we can add is A.8923, which was

the grant of

this same Maurice and his wife Edith to Wix of lands and tithes from

her inheritance (discussed above). But because all

these grants involved Maurice de Windsor it is hard to feel

confident that this is not

simply a member of Maurice's family, about which we know more-or-less

nothing. Clarence Smith (p.111) says

that concerning the first and apparently the earliest of

these, the

"natural assumption would be that Reinald and Robert were brothers of

Maurice". (However if they were brothers, then the descent of the

dapifership to a sister's son was not by inheritance, but rather by

fresh grant, decided by the see of Norfolk. This is possible. And

indeed Edith seems to have had some special status in this inheritance

as she is consistently mentioned in grants by both her husbands.) As to

whether this Reinald

is a member of the castellan's

family, as suggested by Round and accepted by Keats-Rohan, Clarence

Smith seems correct to say that there is "no evidence whatever" for

this "except Round's Harleian Roll" (made in 1582, see Clarence Smith

p.3), and "Round, who so castigated the unfortunate Clark for uniting

all the Hastings families into one, has committed the same sin with his

Windsors". It is a seperate matter that Round and Keats-Rohan also

believe that this Reinald may have been a steward of Queen Adeliza (

Round, Keats-Rohan

DD "Rainald de Windresor",

Clarence Smith p.111, n. 192), because this in itself would not make

Rainald a member of the castellan's family. Maurice himself clearly was

in favour at court (Clarence Smith p.105), whoever he was.

2. William fitz Robert in the second generation.

Landon

(p.176) notes one charter (A.13893) where William the son of Robert, as he was apparently usually

called, was more specifically named as "William fitz Robert

de Hastings".

As Clarence-Smith points out, this charter is a copy of A.13883 with

differences. His children used the Hastings name more consistently, but

not

always, with Robert his son often being referred to as Robert de Aistan

or

Aiston (Landon p.177). Keats-Rohan's selection of the name

"Willelm de Hastings"

(

DD)

to refer to William the son of Robert, is therefore once again a choice

of name which does not seem to represent contemporary records

well.

Keats-Rohan (COEL)

cites examples of this name but all could be her "Willelm

de Hastings Dispensator" (

DD),

the eventual heir to the dapifership once held by Maurice de Windsor. That William

had inherited the dapifership by 1162 (Clarence Smith p.110 n.186), but

he was already of age and serving the king before then. Keats-Rohan

admits (in the

latter entry) difficulty in defining

distinct records that must be

William fitz Robert referred to as "de Hastings". If we follow Clarence

Smith and Landon's interpretation that is because there are very few if

any. Here are the sightings mentioned by Keats-Rohan, where this William may have used the name "de Hastings":

- Cronne/David RRAN III, No. 823.

This is an 1153 charter made at Bridgnorth by Henry Duke of Normandy,

the future King Henry II, with witnesses including William de Hastings and his two brothers

Phillipus and Radulphus. I do not perceive any reason to connect this

to east Anglia, so it could concern men from Sussex (where Hastings is)

or some other part of the country. I also note that Keats-Rohan

apparently is inconsistent because she names "Philip de Hastings" and "Radulph de Hastings" (DD) as William's sons, citing this charter where they are named as brothers

to a William. (Furthermore, as Rosie Bevan has pointed out to me, the

charter is a questionable one. It might for example combine people from

different periods.)

- Dodwell's

Bacton Charter No. 9, which is the same as E40/13984. But Clarence Smith

(p.10) remarks concerning this charter that it is a "striking"

example of the Hastings name being used for William's son Robert, but

not for

William.

- Charter 47 from Douglas Social Structure of Medieval East Anglia

(1927). This is an approximate 1150 Norfolk charter whereby Abbot Hugh

of Saint Benedict Holm was granting land in North Walsham and

"Antigham" to Robert Ludham, brother of Thubert. "William de

Hastingges" is the first witness.

But William the King's dispensator must have had a presence in Norfolk,

where even before inheriting his dapifership, he must have held

Ashhill, as this was connected to the office of dispensator.

- Pipe Rolls, 1161 one entry in Norfolk/Suffolk (p.66) and two entries in London (p.67, p.73).

But this is approximately the period when William fitz Robert died. For

this same year, Keats-Rohan allocates entries in

Warwickshire/Leicestershire, and Northampton as being a different

William de Hastings, who she calls "Willelm filius Hugonis de Hastings" (DD). We will discuss how this William may have had a presence in East Anglia and London, and indeed how he is the same as "Willelm

de Hastings Dispensator".

A.5266, originally

Cartae Antiquae L.2.31.6 (wrongly cited by Clark

p.124

as L.2.31.7 according to Clarence Smith), is a doubtful case where a

William de Hastinkes appears as a witness, but apparently after William

fitz Robert died. If it is not the dispensator of the King, I wonder

if it could be Alexander's son William, who evidently died young, but

whose story seems unclear. According to Clarence Smith this can not be the son of

Alexander, because as a living heir these grants to Ralph should not have been

possible. We can add that there is no evidence his father or anyone in

his ancestry used the surname Hastings. So perhaps more likely it is the dapifer of

Bury and dispensator to the king,

who was heir to the heir of Maurice de Windsor, husband of Edith,

who was

Alexander's sister. As discussed above, his family had an interest in other

inheritances that Alexander held, but which did not go to Ralph de

Hastings of Wix. And he was apparently consistently referred

to as William de Hastings. Clarence Smith (p.13) thinks it could be the

lord William fitz Robert,

despite the document being made "after the death of the Lord William".

He speculates that the Lord William might be the King Henry I's son and

heir, who died 1156 aged 4. (Less likely possibilities include

"Willelm filius Walteri Decani"

(

DD)

mentioned under pedigree 2, but as he probably died without heir. And Jocelin of Brokeland, in his

Chronicle, also

mentioned

a "Willelmus de Hastinga" who was one of the brothers in Bury at the

time of the election of Abbot Samson, in 1182.)

3. Helewise de Guerres.

The

name of the wife of William fitz Robert, Helewise de Guerres, seems to

have been first proposed by Landon, and this was accepted by Clarence Smith and Keats-Rohan.

Her first name is recorded in several charters from Williams own

lifetime (AS.301 = Bacton Charter 9, A.13984, A.13883, A.13893). But for her

surname it was necessary to look at several documents after the

death of William and her re-marriages.

- A.14008 is a charter with her second husband Gilbert de

Pinkenny, but

mentioning Helewise's son and heir Robert. The three of them were

granting part of their tithes in Bildeston (one of the manors of Little Easton) to the nuns in

Wix, as had

been done by in the past by William fitz Robert. Ralf de Guerres was a

witness. Clarence Smith (p.5) reports that Gilbert appeared in the Pipe Rolls from 1163 until 1177. Keats-Rohan mentions that "Gibert

de Pinkeny"

(DD)

during the period of his marriage with

Helewise was "joint surveyor of repair work on Windsor castle".

His

own family's home was apparently in Weedon in Northamptonshire, so it

seems there is a connection between his relationship to Windsor castle,

and

his second marriage. Like Little Easton, his barony was subject to

castle guard at Windsor.

- The Pipe Roll

of 1181, under Yorkshire, mentioned Helewise the mother of

Robert de Hastings, being

married, confusingly, to a second William fitz Robert (see Vol.30, p.45).

This was apparently first understood by Landon. Clarence Smith later wrote (p.4) that "his

connection with our Robert de Hastings is put beyond any doubt by

litigation ten years later, when the prioress of Wix sued William fitz

Robert and Helewisa his wife in respect of the advowson of the church

of Bildeston". This action was settled by William fitz Robert and

Helewisia his wife "in the dower of which said church is founded", and

this was done together with

Ralph de Cornhill and Alice his wife, as patrons of the church of

Bildeston, and also as the people nominated to hold the advowson and

presentation after William and Helewisia. Clarence Smith (p.4)

refers for this to a Final Concord of 15 May 1191, published in Pipe

Roll Society 17, No.8. That Robert de Hastings'

mother was dowered in Bildeston and with its advowson, shows according to Clarence Smith that this

Robert de Hastings had inherited the barony, not from her,

but from his father.

- Landon transcribes a record from the Books of Fees

of 1219, p.282, showing that "Helewisa de Gwerres" was by then clearly

described as a widow who had been married to Gilbert de Pynkiny and

then William

fitz Robert. She was then living in Bildeston and Godfrey de

Louvain was lord of the barony (1199-1226) through his wife. Together

with her in Bildeston was

her daughter-in-law and fellow widow, lady Matilda de Flamville. Landon

says Helewise's first husband would not

be mentioned because the document was concerned with widows under the

King's wardship as theoretically marriageable (despite their great

age). As Landon points out, it appears that Bildeston was used by the

family as a "dower manor" for its widows. (Because of this, Landon

proposes that the widow of Robert fitz Walter de Windsor must have

re-married Hugh de Waterville, who occurs in the Pipe Roll of 1130

under Suffolk, paying for the dower of his wife in Bildeston. Clarence

Smith does not seem attracted to this idea. Instead he suggests that

Helewisa herself had family connections in Bildeston. The two ideas are

not mutally exclusive.)

4. Maud de Flamville.

Concerning Maud de Flamville being wife to Robert de

Hastings, Landon (p.177,

n.6) cites

Monasticon

vi,

p.972,

and

p.1190

and

Rotulus de Oblatis,

p.537.

Clark was

aware of one of these records (

p.244),

but wrongly believed, based on comments of the early Essex historian

Philip Morant, that Robert in the pedigree above was married to a

Windsor heiress (

p.131).

It is already mentioned above that in 1219 she was along with her

mother-in-law holding Bildeston under Godefrey de Louvain, but in

Early Yorkshire Families

pp.30-31

we also find that "in 1233-40, in her widowhood, she gave to St.

Peter's York and the prebend in Dunnington the homage and service of

Sir Godefrey de Louvain for land in Marton". (The source given is

York Minster Fasti,

i, 71 no.25.) Marton was the home ground of this Flamville family,

and evidently the barony of Little Easton had some interest in it after

this point. It is also remarked that in 1251 there was a dispute

between the de Flamvilles and de Louvains about a free tenement in

Norton. In

1231 Matilda de Flamvill and Matthew de Louvain, contested the advowson of Bildeston.

5. Richard de Hastings, his brother Alexander, and Ralph de Hastings in the generation of William fitz Robert.

Although Keats-Rohan only says that

"Ricardus de Hastings"

was "perhaps" a brother of William fitz Robert de Hastings, Landon and Clarence Smith inform

us that a Richard

is clearly named as such in the ancient deed A.13881. Richard

was requesting that his brother William should grant land in Wix to Walter

Maskerel son of their uncle Walter Maskerel. Furthermore there is a

witness named Richard de Hastings who must be this same person. That makes

him one of the first in the family to be found using the name de

Hastings, and possibly the first. The Hastings surname will be discussed

below.

The

brother of a Richard de Hastings named Alexander is mentioned in a

charter A.13760, discussed by Clarence Smith (p.102). This Richard de

Hastings granted 20 acres in Bildeston to Wix, for "the salvation

of the souls of my father and my mother and my own soul and the soul of

my brother Alexander". No other mention is known of this Alexander, who

Clarence Smith interprets as a brother of William fitz Robert. The

charter also has a Ralph de Hastings, not described as a brother

despite the nature of the grant, but appearing in a position

before Alexander de Wikes. Ralph may be the same one who had one and a

half knight's fees under William fitz Robert in 1159 (

Red Book p.730),

which Clarence Smith reasons to be in Bildeston. A Ralph and a

Richard appear as witnesses in that order in Henry II's confirmation

charter to Wix, A.13947. And Richard alone appears as witness to Henry

II's further confirmations to various grants in

A.5268.

Clarence

Smith inserts Ralph as a brother of William fitz Robert and his brother

Richard. But he clearly had at least some doubts about this.

Queries.

Could it be relevant that Landon proposes that Robert fitz Walter's

widow, who may have been the source of the Hastings surname, possibly

settled in Bildeston?This charter

A.5268 (Clark

p.123 and

p.126 calls it

Cartae Antiquae

L.2.31.16, Clarence Smith also refers to it as Bishop No. 448) is

one of the charters mentioned above concerning the grant to Wix of

"Sydriches Hey". It seems therefore relevant that Brooke's charter 1,

(E42/356 i) is a similar document which

includes Richardo de Hastinges

milite

(soldier) as a witness, implying he was a knight. A difficulty arises (Clarence Smith

p.103) because during

the 12th century there was a Richard de Hastings who was Master of the

Templars in England 1154-1180 and an important agent of church and

government, and as such he could be expected to appear on some types of

charters. Indeed it seems he was linked to a Ralph de Hastings, who

granted the Templars Hurst in Yorkshire. It

is not known which Hastings family Richard belonged to, but it is known

that the Warwickshire Hastings also had a Richard (Dugdale thought him

rector of Barwell in Leicestershire). Below it will be noted that a

Richard associated with the Little Easton family is once apparently referred to as a

Magister, which would normally mean a high level cleric in this context.

Concerning the templar, who could presumably be called both a knight and a master (magister), Charter 10, Gervers (1996),

Cartulary of the Knights of St John,

II. mentions him involved in a land grant to the Templars which came

from a William de Hastings. Keats-Rohan associates this record with

William de Hastings "the dispensator", but as Rosie Bevan points out to

me, the templar was also involved with not only a Ralph de Hastings in

Yorkshire (a name found in several Hastings families) but also a Robert

de Hastings in Waterbeach Cambridgeshire, who is named specifically as

a kinsman. The name Robert seems more typical of the Little Easton

family in this period, and we can see how the Richard in this family,

if he was the templar, had an important nephew named Robert.

6. Alice, Agnes and Emma, potential heiresses.

Keats-Rohan,

proposes two sisters to William fitz Robert, Alice and Emma, apparently based

on the lead of Landon (p.176) who mentions them as witnesses

to A.13883 and A.13893, which Clarence Smith describes as copies with

differences (p.10). These were confirmations by William fitz

Robert,

his wife Helewise, and their son and heir Robert, of the grant

of

Alexander de Waham of his wife's share of Wix to the nuns there.

Clarence Smith (p.103) adds A.13780 as another charter relevant to

these confirmations, and another,

A.5266 where they witness a further grant from Alexander to Ralph "at Eistan after the death of William the lord".

With the extra evidence, Clarence Smith adds an extra lady, making it three: "Alice, wife of George;

Agnes wife of Silvester; and Emma, wife of Walter de Exeter" (appearing

in that order of seniority). The implication of their needing to witness this

charter is that they had a potential claim on the properties being

discussed, once Alexander de Waham (the grantor) died. Instead of being sisters, based on timing considerations, at

least concerning the youngest one Emma, Clarence Smith thought it

more likely that these ladies were actually daughters of William fitz

Robert from a first sonless marriage (p.103). Dodwell, p.156, in

her careful style, points out that Emma

could even be a relative of Maurice de Windsor's heir,

"Ralph II de Hastings" (

DD

discussed in pedigrees 6-8 below) again raising the question of whether

Maurice had, in effect, several heirs. I wonder if it is really

impossible that these

three ladies might be daughters of Alexander who had been paid off to

accept this sale (although then presumably the wording of the charter

might have made this more clear). I also wonder, taking on board

Clarence Smith's proposal that Alexander did not have the same mother

as Robert fitz Walter, if they might not be nieces of Alexander who

were more closely related to him than William fitz Robert (descended

from his mother and father and not just from his father). On the other

hand we have no evidence of the surname Hastings in Alexander's branch

of the family, though it is used by Alice and Emma at least, and no

evidence that Alexander had any closer relatives.

Concerning Emma, A.13859 is a grant by the son of an Emma de Hastings

named Ranulf, also mentioning his sister Amabel. This Emma's seal says

"(E)MMA ASTINGE" (Clarence Smith p.103). Landon, Clarence Smith and

Keats-Rohan think this is the same Emma who was married to Walter de

Excestre. Concerning this couple, Brook, p.56 says that Dodwell

believed them to be parents of Ralph de Exon, one of

the claimants to Wix found in

Curia Regis

cases versus Ralph de Hastings (see pedigree 4), and Clarence Smith

agrees (p.7). (So Emma not only had a potential claim on Ralph's land

in Wix, but her son apparently made a claim.) Dodwell (p.156 n.4)

says that their heir took the name Alexander de Hastings, while their

other children used versions of the father's name. Clarence Smith

apparently read the evidence differently, saying their original heir

was named Alexander de Exeter, citing A.13696, A.13697, and A.13698.

It

seems remarkable that Ralph de Exon had a mill in Purleigh, the tithe

and mulcture of which he granted to Wix priory (Brooke Charter 3,

Dodwell p.156, n.3).

Query. Could Ralph de Exeter be the same one who married Amabilis de Hastings? According to sources such as Douglas Richardson's Magna Carta Ancestors, a charter from Fowler Cartulary of the Abbey of Old Wardon,

dated around 1200-1210, says that she had a mill in free marriage in

Blunham. Blunham was one of the lands associated with Hastings

family who were dapifers of Bury.

Rosie Bevan believes this is the same Ralph, and that this marriage can

be helpful in excluding some options - because it implies that Ralph

and Emma can not have had the same recent direct ancestors due to the

strictness of consanguinity rules at this time.

7. The children of William fitz Robert.

Robert de Hastings.

Genealogists using old sources should keep in mind that Robert de

Hastings' position in this tree is another area where, despite previous

authors like Clark getting it right, the harsh judgement of Round

concerning Clark kept people confused at least until Landon, and in

fact the confusion continues. Round and other authors of the past

(going back past Morant at least to a Tudor pedigree in 1582 which

Round cited) were in the habit of claiming Robert married into

this family (though ironically his wife's name was not known) bringing

the Hastings surname with him. Both Sanders and the

Complete Peerage

followed Round without citing him. Landon (p.176) points to charters

A.S.301, A.13883, A.13893, and A.13984 as examples where the son and

heir of William fitz Robert and his wife Helewisa is named Robert de

Hastings, and Landon points out (p.178) that this disagrees with Round.